Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting: Stevie Wonder

“The Greatest Performance in the Wake of Renewed Violence”

Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting: Stevie Wonder at the Key Arena, Dec 3, 2014

On Stevie Wonder and the Masses Needing to Hear The Good Word

This is about the night that Stevie Wonder confirmed who he is and always will be for music.

Almost every black person I saw dressed as if they were going to service. Myself Included. There was none of the sartorial swag one sees in a Seattle megachurch crowd. There wasn't even the standard modern elegance one sees in an audience that goes to a jazz alley show, or the rare quiet storm star who headlines the paramount. I had never seen a mass of black people dress like this -- as if they were from another time or era -- in my life. Even the ticket hustlers wore ties.

I didn't think of it as an aspersion to the non-black people who weren't dressed to the nines. Walking around Key Arena, I found the crowd's mood and energy to be jovial and positive, and one would be a fool to discount that. Yet as others were joyfully buzzing and nerding out to his songs, I couldn't help but be affected by the countenance of almost every black person I saw. So many couples, families, friends and young ones bringing their elders in wheelchairs had the same determined look, as if we had to get to our seats as fast as we could to hear a voice that couldn't come to each of us fast enough.

It was when they filed into their seat in the Key Arena when I got it. We didn't come to the Key Arena just hear a musical master. We came to hear Stevie Wonder deliver the good word.

+

The Importance of the Black Survival Kit

In one of the most brutal and bloody weeks to be black in the history of this nation, we came to hear our people's most eloquent musical champion reaffirm and give witness to our history like he had done so many times before. On a day when a grand jury's inaction transformed Eric Garner's death into a brutal public lynching, we needed to hear Stevie Wonder expand on what Gil Scott Heron called “his black survival kits;" the records we didn’t play just to dance to, but to help us get by in the world.

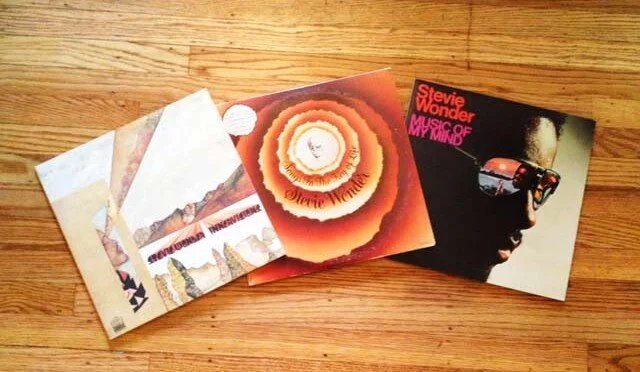

Stevie Wonder’s consecutive string of “Black Survival Kits” -- Music Of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, Fulfillingness First Finale, and Songs In The Key Of Life -- changed him from an ebullient pop star to one of the most important figures in African American history.

Weaving otherworldly melodies with old school gospel rhythmic structures, Avant Garde time changes with repetitive call and response dynamics, and powerful political messages with infectious dance music, Wonder dragged the art house to the church house, and made America pay some cultural tithes.

That string of records deserves to be mentioned with Tennessee Williams’ run of plays, and William Faulkner’s run of novels as one of the most notable and sustained runs of brilliance in American art.

+

The Burden of Talent and Recognition on the Art That Gets Made

Yet, as I first noticed how different Stevie Wonder was from the television performances that I had seen of him in the last 25 years, I couldn’t help but think about how his importance may have burdened his art, especially the art he made during my lifetime.

Stevie’s decline has always been slightly overstated: In Square Circle had “Go Home” and “Overjoyed,” and Jungle Fever, Conversation Peace, and A Time 2 Love had more than a few moments of remarkable beauty. Yet after the commercial failure of A Secret Life Of Plants-- an imperfect, but often beautiful and weird record -- and the political capital he called in to make Dr. King’s birthday a national holiday, “Wonder: The Artist” has always had to deal with and manage the image of “Wonder: The Most Beloved Black Hero on the Planet.”

Like Langston Hughes after his run of early poetry books, he had created a string of work that meant so much to so many people, and yet as a consequence, he wasn’t allowed the space to risk and experiment so that he might create a new run of albums. People did not want him to make new music -- they wanted him to be “Stevie Wonder” -- and the result was that his most recent music only served as a saccharine echo of his early mastery.

There was nothing saccharine about the lack of a trial afforded to Eric Garner after a video camera recorded his murder, which was the first thing on the mind of almost every person I talked to the night of Stevie Wonder’s concert. And the Stevie I saw in person was drastically different from even his prime records.

+

The Stevie I Saw That Night at the Key

The first thing I noticed was the drums: instead of the electronic synthesized insularity that he has leaned on recently, Wonder amassed a conga section of the apocalypse. The power of the drums, along with the virtuosity of Wonder himself, brought songs like “Contusion,” “I Wish,” “As," and “Sir Duke” closer to the earthy power of Curtis Mayfield’s afro-conga experiments, and Gil Scott Heron and Brian Jackson in their prime.

Only Wonder had amplified that sound to make it shake 25,000 people.

The second thing I noticed was Stevie Wonder’s voice. Weary and slightly ragged, it had a drawn-out character far different than the imitable nasal quality that I was used to hearing from him. The iteration of “Loves In Need Of Love Today” that he sang that night had a feeling closer to Donny Hathaway’s guttural power, something that -- in the recitative nature of his vocal runs -- had a history that was as old as west African Muslim prayer chants.

The Wonder that night -- shook, processing, against type -- was the both the most improvisational and culturally nuanced performer I had seen on a stage. Ebullient one moment, full of fire the next, making the Key Arena stomp and then turning around to educate them the very next moment, Wonder played as if he was possessed by something that wasn't him.

Simply put, that night, I saw my people’s greatest tone poet at his absolute best.

+

The Greatest Performance in the Wake of Renewed Violence

I left that concert shaken, moved and determined, and to an extent, I still am. The explosion of violence -- of terrorism homegrown and of a police state -- has continued unabated in the last 7 months. The second black reconstruction called the Civil Rights Movement has ended almost as viciously as the first, and the need for black people to go back to artists who provided survival kits in their music - Aretha, Marvin, Nina, Donny, Gil, and Ray among others - has been a prevalent one in many discussions I have either witnessed or had about the culture.

These records never did the job of setting us free, keeping us safe or giving us equal protection under the law, but they made our lives better by getting us through a day, by giving us beauty and a little slice of ourselves.

Stevie Wonder -- in his emotionally charged state -- gave us more beauty and historical depth than every other performance I’ve witnessed put together. It was the greatest concert I have ever seen or will see, and it would be foolish for me to think otherwise.

+ + +