Interview: Artist Kristian Burford

"The exposure of the characters in a private moment..."

This interview with artist Kristian Burford was conducted over email by NAILED’s Arts Editor, Shenyah Webb.

+ + +

When I first discovered the sculptural installations created by Kristian Burford, it satisfied my voyeuristic tendencies in a way I didn’t know possible while viewing art. I found myself sitting for what seemed hours, studying the mundane, or not so mundane scenes of strangers captured in time, offering me a glimpse to something deeper about the subject and myself. With every detail from the lighting and textiles, to the gaze of his subjects, Burford had me completely captivated. To feed my curiosities, I contacted Burford on behalf of NAILED for a more in depth insight to his motionless scenes.

NAILED MAGAZINE: I am intrigued with your process, specifically that you spend so much time creating one major work (you noted that you spend as many as two full years on a piece before it is considered “finished”) — and yet the work itself is really only suited for a few limited purposes in terms of engagement with an audience: either reproduced photographically in publication, or shown to a limited audience in a gallery or museum. Because you’re participating in the contemporary art world, do you think about collectors? Or where the pieces will end up? Does it matter to you whether or not your work is experienced in person by an audience? What are the limitations of such an art-making practice? Are there advantages?

KRISTIAN BURFORD: When I think about a work I am thinking about how an individual will engage with it. I don’t think of that person in terms of their place in the art world or their place in the world in general, rather, I think of their qualities, I imagine that they are perceptive and open to experience, I imagine that their experience will not be distorted by insecurity or self-interest–other than their desire to feel the pleasure of engagement. I exclusively imagine the audience member alone with the work.

I don’t think about who will own the works–probably because I believe that what is important about an artwork cannot be isolated to the work itself and, to that extent, cannot be bought. It seems to me that what is valuable in art exists only in the minds of those who experience it and, fortunately, the experience of a work of art does not necessitate the burden of ownership. The limitations of making large sculptural works available to a wide audience is certainly something that I have considered but, despite these practical disadvantages, I believe that the physical presence of the sculptural object, as a talisman of an imagined world, has a unique and powerful potential to draw us in to that world as conscious agents.

NAILED: For such detailed bodies of work, it’s such an empathetic and unique approach to primarily think of the individual who is engaging with your work from a more intimate perspective. Do you have fantasies of what they may experience or how they would react being alone with these stories brought to life in your installations?

So many of your stories for the pieces have a dark undertone. Once such individual is privy to the details, do you wish to evoke empathy, sorrow, or anger?

BURFORD: The darkness that you refer to is broadly reducible to a state of alienation whether it be forced or chosen. I think that this state is common to us all: we are all alone in our struggle to establish the fact of our own existence. Most of our motivations, our fears, our ecstasies, are inspired by the pervasiveness of this alienated condition and perhaps our greatest fantasy is to overcome it: to connect with, and so become, the world beyond us; to fall in love. There is a loophole here that has been exploited by artists for centuries: by presenting a profoundly alienated subject (think of a saint in the process of martyrdom) a work can inspire a fantasized connection through identification with the subject’s condition. We fantasize being alone together.

Rebecca (2006), who has recently become a quadriplegic, is alienated even from her own body. She dramatizes this alienation by sadistically objectifying her paralyzed body in a game that she plays with her nieces. The game involves Rebecca being dressed in costume by her nieces while she complements their design with dialogue and facial expressions essentially making herself into a talking doll (a form not unlike the sculpture in which she is presented but that is another explanation). Her body is mortified like that of a saint albeit at her own behest. So, to finally answer your question, the subjects of my work are intended to inspire love (like the Christian saints but without all that annoying virtue).

NAILED: “Rebecca” is undressed, apart from her sheer robe, and yet the children are playing a game with her. In our culture, nudity is mostly private and that would deem inappropriate. It seems that all of your subjects are for the most part nude. When we, as a westernized culture, are faced with nudity we generally explore our imaginations, filling the gaps with sexual scenarios. It seems some of your stories, such as Rebecca, have no sexual connotation despite their nudity. Can you expand on this?

BURFORD: “Rebecca” has been undressed and adorned in the improvised costume of a ballet dancer by her nieces. She is using her nieces for ends that exceed the game itself. She wishes to do violence to the body that she no longer controls. Her nieces are utilized as the unwitting instruments of this violence. They are unaware of the implications of the body’s objectification, the shame of nakedness, of exposure. The only naughtiness that they perceive is that of making a mess and pilfering roses from their grandfather’s garden.

The title of the work concludes with Rebecca awaiting the return to her room of her sister and parents when her and her niece’s production will be revealed to its intended audience–the audience that will recognize the shame that dramatizes her sadistic relationship to her paralyzed body. She is anticipating the emotional disturbance that the scene will cause; the despair of her distraught mother. So, as you suggest, nakedness and the social constructs that define it are important elements in the work.

NAILED: Is this element of privacy instilled into your installations meant to break through the barrier of the social norms we inhabit with each other as humans?

BURFORD: In some fundamental way the works are about the fantasy of being relieved of social responsibility. The characters fantasize being, or are, acted upon by the world. “Christopher” pretends that he is being made to wet his bed. “Robert” strips naked and lies down within the warm membrane of his neglected glass house–a return to infancy within a decrepit and deathly womb.

These experiences are all related to sex in that these same fantasies of acting and being acted upon, transgression, death, and transcendence, are elements, more or less disguised, of any significant sexual experience.

The exposure of the characters in a private moment often serves to fulfill their exhibitionist fantasies. “Christopher” further fantasizes that his bed-wetting will be witnessed by capturing it on video.

There is a dynamic at play here that is particular to the experience of art. Crucial to it is that we as the viewer remain anonymous. The anonymity of the viewer raises the question of voyeurism, which most would consider describes a one-sided power dynamic but, in the case of art, I see it differently. As the audience we can play the role of the imaginary spectator cast within the fantasy of the character, as we are for “Christopher.” We may also, and perhaps this is always the case, play a role that we fantasize for ourselves. From our perspective as viewer, we need not employ all of the defenses that we erect in response to being seen. In this condition our capacity to empathize and identify with a character is greatly enhanced primarily because we need not perform as ourselves.

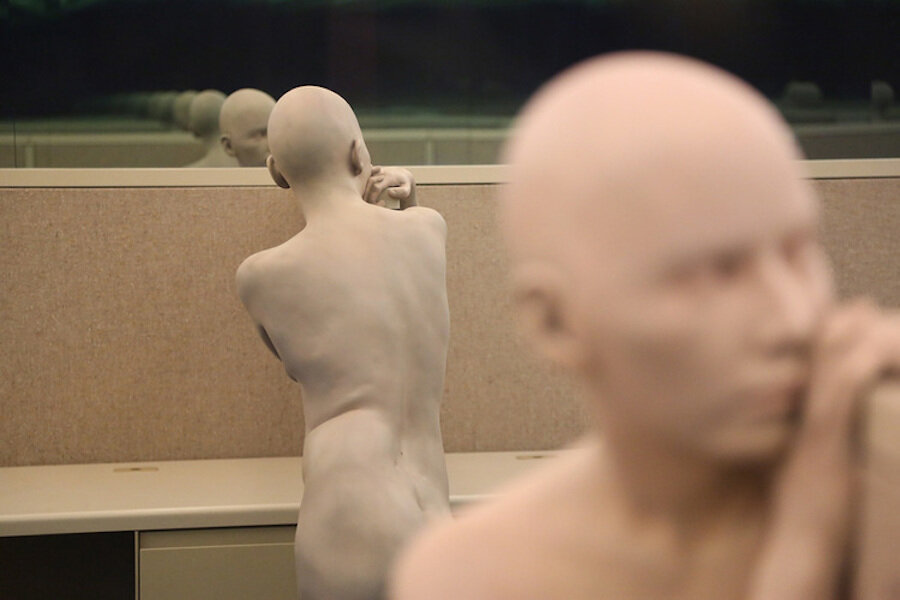

The work that I refer to as Hotel has a title that reads as a stage prompt. We are invited to play the role of a businessman who has brought another man up to our room “after a late drink at the hotel bar.” If we consider that we are in a hotel room on a business trip (an archetype of loneliness), and that we see the man in the room only in mirrors (an archetype of self knowledge), and, what’s more, that he remains in our room when we return “after a day of meetings,” we might come to the conclusion that he is us: that, in the role suggested by the work’s title, we experience a complete identification with the man so that it is we who stare back at ourselves, our own doppelgänger, an embodiment of our own alienation and our own death.

NAILED: Lets talk more about Hotel.

The narration reads: “Last night you brought a man up to your room after having a late drink at the hotel bar. Knowing that you are HIV positive you had sex which caused him to bleed. After a day of meetings you now return to your room.”

You previously mentioned that he plays as “our own doppelgänger, an embodiment of our own alienation and our own death.” When I read the narration alongside the thought of knowing I have just willingly given another man HIV, I have a hard time becoming him. Can you expand more on this piece?

BURFORD: I can understand your resistance. Superficially, in the character that the prompt describes, we use sex as a device of monstrous control which suggests a separation between our character and the man in our hotel room. When I first conceived of this work it was the possession of this control that I wanted the audience to imagine but, as I thought more about the subject, I realized that the victim of this control, the man whom we have likely infected with the AIDS virus, develops a power over us. He came to resemble the model of the virtueless saint that populates my other works–only this time it is we who mortify his flesh by infecting him with our disease (which was fatal during the period in which the work is set). His becomes the power of a being who transcends his body and anyone who presumes to project power over it. I fantasize a complete, sublimely tragic, communion of beings in which all social and moral judgment is irrelevant. Under the influence of this communion, to fuck him is indistinguishable from fucking ourselves. The way he looks back at us is critical to this possibility.

NAILED: When was the last time you NAILED it?

BURFORD: Hmm…I took my dirt bike out to the desert a few weeks ago and I felt like I nailed a few corners.

+ + +

Kristian Burford has a show opening on Friday, September 11th at Samuel Freeman Gallery in Los Angeles. For more information on the exhibition, visit the gallery site: here.

Kristian Burford was born in 1974 at Waikerie, South Australia. He studied at the South Australian school of Art between 1992 and 1995 earning a Bachelor’s degree with Honors. In the four years following he taught at his alma mata in the capacity of a tutor and exhibited in Australia including multiple museum surveys of Australian contemporary art. In 1998 he was awarded the coveted Samstag visual arts scholarship which enabled him to complete a Masters degree at Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California in 2002 where he studied under Mike Kelley, Stephen Prina, Sylvere Lotringer and Jan Tumlir amongst others. Since that time he has exhibited consistently in the US and Europe. Burford’s work was included in Mike Kelley’s re-staging of ‘The Uncanny’ at The Tate, Liverpool and MUMOK, Vienna. Other major exhibitions include A Triple Tour: Collection Pinault at The Conciergerie, Monument Nationale, Paris. His work is represented in the Pinault Collection, France, and the MEFIC Collection, Spain. Burford Lives and works in Los Angeles, California.