In This Economy by Kirsten Larson

“either give the house back to the bank, or wait for them to foreclose”

Fiction by Kirsten Larson

+ + +

About ten years ago, before the market crashed, I had drinks with Shelley, Drake’s wife, in the bar at the Ironwood Country Club while Drake and my husband John golfed. It was right after we signed the closing papers on our home. Drake was our loan officer. I figured Shelley’s part of the business was to have drinks with everyone who signed a loan with her husband.

Shelley had fluffy blonde hair with a figure like a pencil. I didn’t see one spot between her white white teeth that she could drag a strand of floss through. I knew John thought it would be fine if Shelley and I were friends. I saw her at the Country Club the two other times I went there, before John and I divorced, but I never had drinks with her again.

She held her sweating chardonnay glass by the stem. Each time, before she took a drink, she swirled the white wine and sniffed. I wanted to ask, isn’t that what you do with red wine, but that’s not how I am.

What she told me forever pressed that day into my memory—Drake made $1,000 for every $100,000 in mortgages. Drake financed a couple of half million-dollar mansions a day at that time. All he did was take our application, and he made what I’d made in a month as a teacher.

Every time the rates fell—and back then that was monthly—Drake had his assistant plug the numbers into the computer, and out spit a preapproved application for a refinance, only Shelley said refi. The assistant would then call the customer and tell them they’d been approved to refi at a lower rate—no charge—with a lowered monthly payment, all they had to do was sign papers. Drake made $2,000 per refi. She said, he did 60 last month, swirled her glass, and took a sip of her wine. I was busy doing the mental math that was their monthly income, so it only occurred to me later that schmoozing might have included her asking me one question about myself.

Shelley said John and I should consider buying investment homes to rent. When she said we have five homes and are looking to buy a sixth, she clicked her plastic, white-tipped, fake nails against the table one-two-three-four-five, and then made one extra click, for their next investment home. The glassy sounding tick of her nails fascinated me. I wanted them to have ten homes so I could hear more ticks.

I couldn’t take my eyes off of the round diamond on her left hand. It was wider than her finger and caught light from everywhere, even in the dark of the bar. My own diamond was a third the size and even so, the size embarrassed me so much I hardly wore it. When I did wear it I’d often turn the diamond into my palm. John thought I should be proud to wear it. He said it was a symbol of success. Success for whom, is what I wondered.

+

John and I had lived in the house for three years when Drake called to set an appointment to discuss the mortgage. It was odd Drake called our home instead of talking to John at Ironwood, where they golfed every week, but I agreed to go.

We’d been so excited with plans when we bought the house. Even so, three years later we still hadn’t furnished any of the spare bedrooms. The formal living room had nothing in it but a blue Oriental carpet. We planned to have one child for each bedroom. So far I’d lost three babies, all at the end of the second trimester. Fertility specialists were no help. My doctor said the odds of me holding onto a baby were slim, and we should consider other ways to parent.

In the closet of one of the empty bedrooms I kept the three tiny urns, one blue plastic, one white metal, and one pink plastic. I could neither look at them nor dispose of them.

We gave up the plan to be parents like we gave up the plans we had to go into the Peace Corps after college. Or maybe the Peace Corps was my plan, I don’t remember. Just like I don’t remember when John slipped into his country club life or when I slipped out of a life where the Peace Corps sounded like the right thing to do. I just knew that if we had children, I would not want them to spend time at a country club. I would have put my foot down about the country club if things were different, but I was glad John had somewhere he loved to go.

+

When I asked John why we had to meet with Drake, he said something like it was no big deal, we were just going to discuss the balloon payment on our mortgage. The balloon payment was due year five.

The surface of Drake’s desk was glassy as a lake. Just like the last time we were in Drake’s office—when we got preapproved—there was not one piece of paper on his mahogany desk. At the time Drake preapproved us for a one million dollar mortgage, which was ridiculous. We were looking at houses a quarter of that amount. I remember Drake said real estate is a solid investment, you should always have a mortgage that makes you uncomfortable.

Drake had a face like a pie, wide and pitted. His skin was tan year round. Like John, he wore dark slacks and a white buttoned-down shirt. Unlike John, Drake wore an oversized, sparkling Rolex on his tanned wrist. The watchband hung on him. He had this move where he’d flip the face around by making a quick chop with his hand. When he was still, his head cocked at an angle, like a pose. His teeth were neon white. Drake had a certain presence.

John and Drake referred to each other as ‘Buddy’ so often during that meeting that I felt my mood cross a line I wouldn’t be able to come back from, which usually meant I’d say something I might regret later.

Drake leaned across his empty desk toward us and spread his hands out for emphasis, “Hey Buddy, sorry to do this, we just need to know your plans with the balloon, you know with the market the way it is buddy, we’re calling in ev-ery-one,” he said.

John leaned toward Drake with his golf-course personality, “Oh, I know Buddy, this economy. Jay-sus,” he said.

Who was he, my husband? Repulsion pushed my heart rate up.

Like every other time I felt this feeling, I made myself list things I liked about him. Cowlick was all I had. Then I remembered he always asked for the Ordinary Guy haircut from his barber. Ordinary Guy included a squared off back of the neck, which I told him I hated, but he got the same haircut every six weeks.

I took cowlick off my list.

John worked in commercial real estate. He developed new construction, mainly office buildings. He’d started to spend more and more time in the office, trying to impress the owner, insurance against being the first one cut. At that time the economy wasn’t at it’s worst yet. John wouldn’t lose his job for three years—the same year we separated.

I couldn’t stand one more buddy, “That payment’s not due for two years,” I said, “why are we discussing it now?”

I saw my tone cross Drake’s face. His eyes slid to John, “Man, they are pressing us. Everyone is pressed, even me. I have rentals I might lose over this economy, Buddy. I might lose it all. So sorry. We could try to refi but with that jumbo loan…the way it is right now, you’d have to make, oh,” he looked toward the solar calculator out of reach to his right, “about four times what you were when you applied, just to finance that balloon. Compliance with these new regulations is im-possible,” Drake said.

He picked a long, silver pen out of a holder with a plaque that faced toward us engraved with the words, “World’s Best Dad.” I supposed that was one thing to get the man who had everything.

He twirled the pen, “Lots of folks selling. Now’s the time,” He said. His nails were buffed.

I knew jumbo loan meant over $500,000. “Are you saying we could lose our home if we can’t tell you right now how we plan to repay something due in two years? We’ve never been late, not once,” I said.

The smile was gone from John’s face but his voice was the same old bullshit-friendly John. He wasn’t one to make people uncomfortable, “No, he’s not saying that, hon. We have options. I get it, Bud. I get it. We’ll talk about it and get back with you,” John said. He leaned over and patted my knee.

I shot him a look that I hoped said die. I felt like he sided with Drake, and didn’t get that this balloon thing meant trouble. John’s soft hair flopped onto his forehead from the stupid cowlick, like a young boy. I thought about how he’d take losing the house and so didn’t say more.

Drake put his hands on the leather arms of his chair and pushed off. “Okay, sure, sure. That’s great Bud. They’re giving us two weeks for an answer,” He grabbed John’s hand, “you golfing on Sunday Buddy?” From behind the two of them it looked like Drake was trying to drag John to the door.

+

As a teacher, I had three months off of work every summer. Some of my coworkers traveled the world, some wrote books, or painted their homes. It was the first spring I wasn’t pregnant, planning to get pregnant, or boxing up little baby clothes and crying. I’d had so many ideas for the summer, but I’d done nothing I planned to do. I was going to hike Big Bear. I was going to ride my bike along Hwy 101 from Los Angeles to San Francisco and take the train back. At the very least I was going to take a Pilates or spinning class every day at the gym I’d planned to join.

What I did instead was lay around and watch TV. I got up with John every morning, made coffee, and acted like I was going to do something, but then went back to bed and slept until 1:00. I slept my deepest sleep between 7:00 AM and 1:00 PM.

I had two pleasures—sleep and TV shows. I’d get out of bed at 1:00, groggy and drugged, and then sit and watch more TV until 4:00. First talk shows, then Perry Mason, finally old movies. When I could waste no more time before John got home, I took a shower and cooked something for dinner. By the time he got home I was on my third glass of wine.

When he asked I made up lies about Pilates. I made up lies about hikes I never took with teacher friends I didn’t have. I lied about yoga, spinning classes, the books I never read. John might have noticed if he hadn’t been so concerned with the economy.

Turned out we only had one option that would satisfy the bank concerning our balloon payment—we had to sell our home.

Our realtor had an expert stage our house before we put it on the market. She took all signs of us out of our home. She had us put away our family pictures—she said a prospective buyer wants to imagine they live in your home.

For a few weeks, every time we took a shower we straightened the towels on the racks, squeegeed the glass shower enclosure, and put our clothes in the hamper in the walk in closet. It ended up we only had one viewing—the first week we listed it—and that one viewing was a realtor looking at her competition. Three weeks later I again hung my bathrobe on the back of the door, and then left my wet towels slung over the shower enclosure.

The fine print of our loan said we had to let the bank know our plans for the balloon payment 24 months before it was due. Since it wasn’t going to sell, our choices were to either give the house back to the bank, or wait for them to foreclose. Unopened notices in large, white envelopes piled up on the table by the front door.

I waited for something to happen.

John and I hadn’t discussed it at all. But I wanted to tell him - had we bought a less expensive house, like I wanted to, the bank would have worked with us as what was happening with a lot of other people. My left hipbone hurt from sleeping with my back to him night after night.

+

That summer was almost over when the construction started next door. I had only two more weeks before I had to go back to work.

I looked at the clock, 11:00 AM. Sounds of voices, shouting, and metal clanging made it through the window. Soon, there were trucks beeping, and other sounds I couldn’t identify. I pulled the pillow over my head.

Then I heard what sounded like a tractor. I rolled over, stood up, and straightened my sore back. At the window I opened the light-blocking curtains a bit to look next door. A couple from India had just purchased the house. She had beautiful jet-black thick shiny hair. Every time I saw her I wanted different hair. The husband worked at one of the tech companies close by. Irvine was full of them. Our hope had been that someone coming to work at one of those companies would buy our home, but there were nine identical homes for sale in our neighborhood priced less than our mortgage. The Indian couple bought their brand new home from the builder for less than we owed.

The economy was all over the news—news that said people like us had caused the crash—people who bought homes they couldn’t afford, and then stopped paying.

Next door, some guy in a yellow hardhat maneuvered a backhoe off of a big trailer parked on the street. It said Deere in white letters on the long, black arm that held a toothy bucket.

Two other men unloaded pipes and bags of something from a truck. I counted five cars on the street. Definitely not a one-day construction job. I squinted to read the logo on a truck—Serenity Pools. Blood squeezed at the sides of my neck—they were installing a fucking swimming pool. I lay back down and tried to breathe evenly.

With only two weeks before work started I’d made the decision to embrace my inaction. I hated the thought of going back to work. I knew that once I was back in the classroom, I’d feel okay. But that year was different in a way I could feel in my body. I was 35 and had been a 7th grade teacher for long enough that I’d started to run into past students who had babies of their own.

At the end of that last school year, on my 35th birthday, we had a cake in the teacher’s lounge like we always did for birthdays. It was the same teacher’s lounge that held the celebration of my first pregnancy, and held the silence that came with each of my miscarriages. I blew out the candles on my sheet cake and said, “Thirty-five. Huh, I can’t believe I’m halfway to forty.” Mike Wilson, the new 9th grade science teacher said, “Actually, you’re half way to seventy.”

He and I were the only two who laughed. He laughed because he didn’t know about my miscarriages. I laughed from the relief of it. Pity had left me lonely at work.

Next door people banged, clanged metal, and shouted. I felt my heart beat up in my ears. All I wanted was to sleep and watch TV in peace for the next two weeks. Two weeks in the house that wasn’t going to be my house for much longer, before I had to go back to work. Back to teach 7th graders, kids full of nothing but possibility.

I scissor kicked the comforter off, got up and rooted in the dresser for something to cover my tank top and underwear. I pulled on a pair of John’s shorts.

A fucking swimming pool, in this economy.

I went downstairs, past piles of unsorted laundry, and stacked up newspapers. I walked fast past windows hazy with grime. I could feel my ass jiggle from the months of doing nothing. Dishes were piled on either side of the kitchen sink. I could smell the funk of my hair, which hadn’t been washed in days. Empty wine bottles glinted ruby and emerald on the counters. I kicked a bag of dry cleaning John kept by the side door. I flung the door open, stepped onto the driveway, which separated our house from the neighbor’s. I put my arm across my eyes to block the hit of sunlight and heat. My head felt full of water, and I stood still to try to stop the spins. I let hot driveway pavers burn the bottoms of my feet.

When I looked up, I counted ten men, all wearing logoed polo shirts and khaki construction shorts. A few stood near the side of the house, more unloaded tools and such from the truck, and some looked at papers, probably pool plans. The guy driving the backhoe maneuvered at the bottom of the neighbor’s drive.

I walked over and stood in the middle of their driveway. My breasts moved against the thin tank top. The sun burned the top of my head, but I could smell the clean of the ocean, the edge of fall.

From the top of the driveway I watched Serenity Pools gear up. No one looked at me. For the first and last time I considered maybe just going back into the house.

But then I saw the car.

A shiny, black Audi pulled to the opposite side of the road. My new neighbor with her river of black hair got out of the passenger side, a smile on her face. She looked up at the house for a second, then opened the back car door and bent down, into the car. Her hair slid down around her.

There, from the back of the car, she lifted up a baby up to her hip. The baby looked about a year or so old. The husband—the dad—stood up out of the driver’s side of the car, and then closed the door. The pink of the child’s dress was patterned with small green and white flowers. The smooth darkness of her beautiful little shoulders look like burnished mahogany against the strap of her sundress. The baby wore tiny, pink loafers on her dangling feet.

Tiny, pink loafers.

Maybe I snapped. Maybe I lost my mind. Or maybe I just got real. Looking back, I can honestly say I don’t know why I did what I did.

The rumbling excavator sputtered and jerked up the driveway. It stopped moving about 30 feet from me. I smelled the oily, metal, gas of it. The driver sat up high in a metal cage, although I could barely see him behind the big bucket arm. White jets of smoke blew out the exhaust pipe to the top. He yelled, “Lady, you’re going to need to move. I need to get back there,” his hand waived to indicate behind me.

I could feel the rumble under my feet. I stepped my left foot out and held my hands out to both sides of me. I made my body like an X. “Not moving. This needs to stop,” I screamed. Spit flew out of my mouth. The pressure from my scream pushed at my eyes and my neck.

“Not moving, you need to go. Go. Leave here,” my heart made a fist hard in my chest.

The three men who stood near the house, about 40 feet from me looked at my standoff for a long moment and then put their heads together. They were tall, white men who looked like they worked out in a gym, thick necks, arm muscles pushed against sleeves, blonde hair, tanned legs. Bodies like the bullies I avoided in high school.

I knew they’d leave. It was embarrassing, yes, but I knew they’d leave me in peace; they’d wait until John and I moved out. They would be kind and understanding and wait until after the foreclosure to install our neighbor’s new swimming pool.

Their heads turned toward me at once. The shortest one walked toward me, hands on his narrow hips. At about ten feet away he stopped, “What’s going on?” he said. A wad of blue gum rolled between his even white teeth.

The ridiculousness of it, what could I do? I’d already made a scene. I had to commit fully or humiliate myself and retreat. I kept myself in the X. “You need to go. I’m just warning you. I’m not moving. You will have to kill me, and I’m okay with that.” By the last word I was screaming again.

What I wanted, what I expected, was for him to try to talk with me. Reason with me. My plan was then to make up something so they would see they had to stall. Not forever, just for two weeks. Until I could figure out what our life was going to look like after our house was not our house anymore.

The man turned and looked at his coworkers and gave a nod. He turned to me, “Where’s your keeper, lady?” He didn’t raise his voice much, but I heard him clear over the excavator. His eyes were flat.

He walked up to me like he walked into a 7-11, paced, no fear. I thought he’d stop to talk, but when he was beside me he bent quick and put his arm around my waist. For a second I thought he was going to hug me. I could have used a hug. I smelled cigarettes, and sweat, and soap, and man—how men smell when they are in their 20’s. I felt how hard his arm was against my stomach. “What are you doing?” I yelled.

He jumped a little and tightened his arm more, banding it under my ribs. Only my toes bounced along the pavement. He jumped and tightened again, so much then, I couldn’t get a breath. Maybe it was some gym-jujitsu move he’d been dying to try on someone.

I pushed against his arm, but it was like a cinched metal rod.

In one quick motion he jerked me sideways off my feet. I didn’t hear my ribs break, but felt the sharp pain from my side to the middle of my chest. Every bit of fight I had left my body. I went limp, terrified of what else he was capable of. The pain where my body weight pressed my side into his arm was excruciating.

Maybe I fainted a little.

I tried to push against him to take some weight off of my ribs. My hands slid against his shorts, against his hard, gym-corded thigh muscle.

I wanted to scream, but I couldn’t get a breath. Air went in and out in fast, tiny movements. The pressure in my chest was my own breath, trying to avoid movement and more pain. He carried me only about thirty feet. Thirty feet of the worst pain I’d ever felt.

In my driveway he dropped us both to the ground, hard. He was on one knee beside me. He jerked his arm out from under me like I was a bag of dirt. The effort had him breathless. I rolled on my back and hung onto his arm.

He bent his face near my head, “Bitch, this is your house, why don’t you stay where you belong,” he said.

I held onto his arm. He pulled against me in effort to stand. I couldn’t get a full breath for the pain. I coughed my words out with as much air as I could give, “Do you know who I am?” I asked, “Do you know who I am?”

+ + +

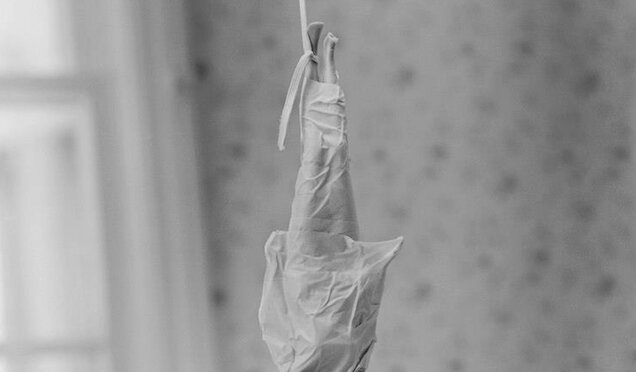

Header photograph courtesy of Alison Antario. To view more of her work, go here.