There Are Too Many Ways to Hurt by Tracy Dimond

“why do we break each other? Is it like cutting hair off dolls?”

Review by Tracy Dimond

+++

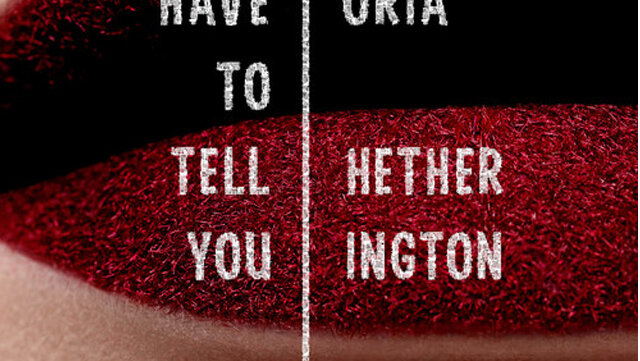

Victoria Hetherington Reminded Me That There Are Too Many Ways to Hurt People, a review of I Have to Tell You (0s&1s, 2014) by Tracy Dimond

People share stories as attempts to open their world to another person. Baggage builds, age adds to the narrative. How is there enough time to share everything you need to? There are so many distractions. This worries me. Victoria Hetherington seems worried too. While people try to share their stories, their behavior often explains more than their words.

There is something purer about childhood. As age accrues, reflections haunt interactions. It is a time you rarely consider your body, unless you can’t catch a firefly or jump off a swing. Countless writers have expressed this. Here are two examples:

-- Sylvia Plath wrote in The Bell Jar, “I thought how strange it had never occurred to me

before that I was only purely happy until I was nine years old.”

-- Leigh Stein wrote in The Fallback Plan, “I mean, when I was little, all my friends were like me.

I didn’t have any other life to compare mine to, so yeah, I think I was happy.”

I reference these books because they influenced my reading of Hetherington’s book. I ache for characters that struggle through developing a sense of purpose. If we live to love, why do we break each other? Is it like cutting hair off dolls? Is it like burning toast to watch it change?

The characters in Hetherington’s I Have To Tell You battle. They battle each other, their own minds, their own bodies. The characters think they are past playing with animals, but they torture each other. Sometimes it’s accidental, like letting a toad drown. Sometimes it’s intentional, like using insecurities to cut before the other person can do the cutting.

An idiom goes “you wear your heart on your sleeve.” Maybe a sleeve is an accumulation of knowledge and perspective. But heart, in all levels of hurt and hope, is also in habits, defense mechanisms, gaze. The performance is learned. We spend adulthood trying to perfect our roles. It’s a means of protection. So many relationships are built on attempts to protect.

Sherene, a mid-twenties beauty, knows her youth is fading. She uses her visual power as much as possible because she understands that a body is part of the self. She tells the other characters that she is aware of her power, but she won’t stop. Sherene is that girl you want to hate, but then you realize that her allure is forgettable. Her performance builds to a lonely last act, an end she anticipates. Can you blame a woman for using what she thinks is her only strength?

Why do we ask each other, How are you? rather than How is your age? If you are young, maybe your luminescent skin can hide some truth. Abuse and environmental toxins haven’t dulled your hair. In the novel, the forty-plus Anna says, “By myself I’m fine, because nobody’s looking...” But when others are factored into the day, you have to present a self. Assert this through alterations.

A body has a narrative. Hetherington puts the characters through everything – starving, purging, and drugs, which eventually compose their identities like a new haircut. They attempt to explain themselves in the dialogue-heavy novel, but the multiple character perspectives show that everyone is “found out” on some level. Say what you want, behavior screams.

These characters create discomfort because pieces of them are in all of us. How many times have you felt so in love you would do anything? It’s terrifying. Hetherington captures raw love and hate. It’s easy to say you would do anything for someone, until they tell you to never call. Is that a form of protection?

Protecting lacks honesty. I would rather you hate me, tell me the truth, than think you need to fight against my emotional fragility. My last long term partner tried to protect me. He wanted to stay friends, but shield me from what he really wanted. How is that real? Hetherington’s characters push against uninvited nurturing.

More specifically, protecting is false. No one is available every moment. Emergency hotlines are a safer choice than a person with her own agenda. It would be lovely to find two people present while together. Too many moments are ruined by attempts to protect a concept.

What if more people screamed what they needed? What if they let go of roles? What if they burned structure and ran? Tom, in his late 30s facing death, wants to end on his terms. Sherene softens when she allows Tom to be.

Tom leads us to the last joke of existence: escape. Interactions connect a web of perspective that cannot be ignored. I Have To Tell You jars the reader into acknowledging these interpersonal influences.

Find Victoria Hetherington's I Have to Tell You, here.

+ + +

Tracy Dimond co-curates Ink Press Productions. She is the author of Grind My Bones Into Glitter, Then Swim Through The Shimmer (NAP 2014) and Sorry I Wrote So Many Sad Poems Today (Ink Press 2013). Her work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Big Lucks, glitterMOB, Coconut, Everyday Genius, Hobart, and other places.