The Twenty-Year Lie by Heather L. Levy

“Nothing is free, least of all female sexuality”

Personal Essay by Heather L. Levy

+ + +

It was perfect. It was everything I hoped it would be. It wasn’t like her story, one knee wedged in the backseat of a musty car, the other leg flopping against the passenger’s seat like a dead frog with some boy grunting on top.

My first time was special, and not just in the usual sense that it was the first time. My first time had meaning within the deeper realms of sexual encounters and comparisons. My first time was a well-executed plan down to every detail.

I was never one to give a play-by-play of my so-called deflowering, although I always enjoyed hearing other women’s horror stories. Their accounts were usually entertaining, but I couldn’t relate to their tales of popping cherries after prom or banging in their parents’ basement. For one, I never had a basement. For two, I secretly enjoyed keeping my first time to myself. I didn’t know it then, but there was a third reason why I kept quiet about my own story.

Fast forward and I’m a mother of two impossibly beautiful and bright kids. Whenever the oldest, our twelve-year-old daughter, asks those sticky questions so many parents fear, I channel my mom, a woman who might’ve been a closet nudist for all I knew. It always surprised me how I could never surprise her in our conversations.

When I told my mom about my first time, she made me hot chocolate and cheese toast as she talked about condoms, STDs, and how it was lucky I was already on birth control for my heavy periods. She never told me about her first time, but I know she was a virgin when she married fresh out of high school. I imagined her first time as two slices of white bread, no condiments, gently rubbing together.

I wasn’t surprised when my daughter broached the topic one evening. Like me, she finds shelter in humor, so she approached the subject like a standup comic testing out new material. I almost didn’t catch what she was asking through her nervous giggles. I had prepared for this inevitable talk, the story I withheld from others but knew it would be impossible to withhold from my own daughter. So, I started the story the same way I told it to myself.

Once upon a time, there was a sixteen-year-old girl who worked at a restaurant. There, she met the wittiest person she had ever known up to that point in her life. He wasn’t like boys at her school. He made her laugh and told her she was beautiful and intelligent. She thought she was in love and wanted to tell the world, but the man told her everything had to stay quiet at work because some people wouldn’t understand their age difference.

Here, my astute daughter stops me. “Wait, mom,” she says. “How old was this guy?” I pause, knowing there was no way around it. Twenty-six, I tell her. Her expression changes the tiniest bit, the wheels turning in her ever-curious mind.

So, the girl told only a handful of friends from school about the man. No one at work knew, or that’s what the girl thought. A few weeks went by of making out in secret spots and eating at various restaurants after shifts, all paid for by the man. One day, the man told the girl he had a surprise for her birthday. He suggested she tell her parents she was staying the night with a friend, and the girl thought he was maybe planning a surprise birthday party. She thought of when he took her to one of his friend’s parties that lasted half the night, the one where she tried mushrooms for the first time. She remembered spinning, arms out, laughing at how everything sparkled.

“He gave you drugs?” my daughter says, her eyes wide. No, I tell her, the drugs were at the party he took me to, and I made a poor choice. She doesn’t look convinced, and I decide not to tell her she’s partially right. Yes, he did give me drugs at the party, but I’m the one who took them, and I mostly danced around in the front yard with another girl my age. This is another partial truth. The other part is fuzzier, but I recall hands between my legs, in my underwear, and a tickle wanting to explode but never fully igniting.

After work on the girl’s seventeenth birthday, the man takes her to dinner, just the two of them. They eat, and when they leave, he points to the hotel across the street and says that’s where they’re going, to the top-floor suite. The girl imagines her friends in the hotel room, waiting to jump out and shout “Happy birthday!”

There was no one waiting in the hotel suite.

There was a bucket of ice with champagne and two glasses next to chocolate-covered strawberries. There was a towel on the bed. He gave her a velvet box containing a matching necklace and earrings—silver butterflies—and she didn’t tell him she could only wear gold-plated posts because anything else made her earlobes itch. There was a towel on the bed. He told her he wanted to surprise her, to be alone with her without his friends around. He wanted her birthday to be memorable. There was a towel.

My daughter says nothing at first. Her face tells me everything, and I don’t want to look at her. Finally, she says, “Wasn’t that kinda, I don’t know…wrong?”

I want to scream at her and say no, my first time was special, and not just in the usual sense that it was the first time. My first time had meaning. It was a surprise. It was a well-executed plan down to every detail.

I imagined my mom’s first time again, the time she never told me about, the two slices of white bread pressing and pressing, crumbling onto bedsheets. Was sex ever a choice for her? Was it simply expected?

When my mom made me hot chocolate and cheese toast, slightly burned on the edges the way I like it, she didn’t ask me what I had wanted in that room with champagne and strawberries. She listened to my story and said the thing I would tell myself for the next twenty years: your first time was magical compared to most.

Yes, I tell my daughter, it was wrong. My first time was wrong. It was not magical. It was my choice, my story, but it wasn’t my script. I thought the two options were rape and consent, but there is a third sinister option: quid pro quo. Nothing is free, least of all female sexuality.

I want to tell my daughter so much more about those gray areas our mamas’ moms never told them about. Where is the line between informing and terrifying? I think it’s in the slight crease between my baby girl’s eyes. So, I stop and hold her against me. If I squeeze her enough, she’ll be safe. I tell myself the lie every day. If I don’t, I might break and she will see.

Still, I whisper to her, to myself: it’s your story, yours and nobody else’s. Learn how to write your own script. If you don’t, someone else will write it for you.

+ + +

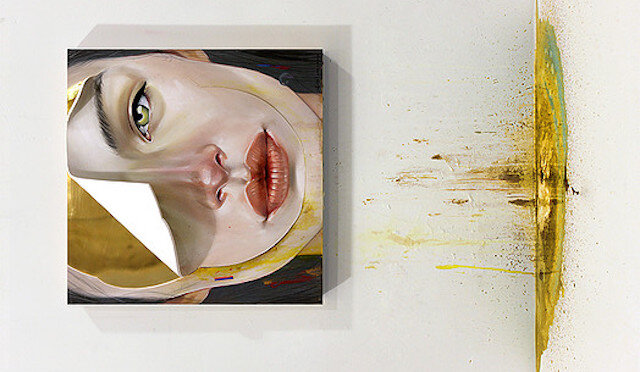

Header image courtesy of Erik Jones. To view his Artist Feature, go here.

A born and bred Oklahoman, Heather L. Levy is a graduate of Oklahoma City University's Red Earth MFA program for creative writing. Readers can find her most recent and forthcoming work in numerous journals, including Crab Fat Magazine, Prick of the Spindle, and Dragon Poet Review. She also authored a nonfiction series on human sexuality, including "Welcome to the Dungeon: BDSM in the Bible Belt," for Literati Press.