The Poetry Closet: Zia Pollis

the first question

What is ‘The Poetry Closet’?

That’s probably the first question you may have. In short:

I’m a poet.

I’m poor.

I live in my friends’ closet.

To cope with this reality I have dubbed this place The Poetry Closet (for there is poetry read and written here) and am now naming this new, semi-regular column in kind (for here too will be a place where poetry is read and written). There will be discussion of poetry. There will be performance of poetry. Maybe there will be other things. Tah-dah!

Originally I planned some sort of introduction episode, a who-am-i type of thing, but things happened and that will have to come later if at all. Pay no attention (for now) to the man behind the curtain (no, really, the closet is separated from the living room by a curtain). What’s important is poetry and in this episode have I got a poet for you…

Zia Pollis is powerful. Zia’s poetry has got a body and is not afraid to live. I met Zia in Portland after hearing her perform at an open mic and thought to myself, this is the kind of visceral poetry I could read and listen to again and again. So naturally I want to share her poetry and her thoughts with you. Enjoy.

And please do support the living artists (send them money if you can, buy their books and share their work).

Dead artists really don’t need the money.

Without further ado:

Zia Pollis

Two Clean Virgins

Winter, and the laundry line is rigid against the sky,

boney with stubs of ice,

milk teeth

from the suckling mouth of this,

the witch season.

The washing machine

awakens from its dreams of slippery gears and sockets.

The knob turned, the body of the old woman

fills pale and tender with a belly of snowflakes,

crystals powder blue, the chemical dew of bubbles

frozen in their translucent bloom. These frosted eggs

suspended, as the spin cycle rattles shingles off the roof.

I wash my clothes in the shower.

Raising a frothing soap on my scalp, these hands

rub raw water down

to my feet where each toe is a laundress

curling the drain.

My sister slings denim over her naked thigh and slaps

the bleeding dye out of every living fiber. Poly, Nylon, Rayon

this triad of angels seeps and swells in the onslaught

of our hand, foot, and finger prayers. We kneel and we knead—

the sweaters and grey bowls of bras

fill with a swill of sweat,

ash from the fire and hair from the dog.

This is the ritual of virgins

more bestial than vestal. Soft girls in hard water, pulling

the wet weight of our modesty

out of the tub

to be hung on the back of a kitchen chair.

NAILED: What is your “poetry closet” (metaphorical or literal)?

Zia Pollis: My earliest writings were prayers. I was not raised religious, but I was anxious from an early age, so I believed I could seal the fate of my world if I captured it in the right words. My loving mother never discovered that I wrote many of these first, protective poems on the mattress cover of my canary yellow twin bed. There was no safer feeling for a seven-year-old than sleeping on a litany of smudgy, Sharpie poetry. These days I use notebooks, mostly.

N: What are the best, the worst and the weirdest moments of your poetry life?

ZP: Poetry at its best is so effortless that we forget the mechanical bulk of syllable, line, and stanza, and instead live in the sensual experience of sound and image. Personally, I am always pushing towards a poetry that feels like it is a living creature: visceral, muscular, hungry, and wicked with animal intelligence.

At its worst, poetry feels paltry, and I am tortured by my attempts to make it meaningful in the eyes of some invisible critic. It feels like just words, and that is terrible to me.

In the squirming maneuvers I do to return my writing to myself, I sometimes stumble into the weird worlds that only poetry knows. When I can’t write something new and my inner eye is getting buried beneath the static snow of the white Word Doc page, I go back to my saved drafts. I find all the 3:33 am wrigglings of words splattering into computer documents or notebook margins. They are full of loving curses, captured syllables, strangled images, and sanctified swear words.

The Apples have Novembered on the Tree

swollen and ruddy as boxing gloves

pummeling the dirt

when the wind blows. Crow and Raven,

attend to the treetop

where human hand fails to reach. I watch

the aging world, curled and brunette, from the kitchen window.

I steam pink onions in pale oil

stirring until they waste

into caramel sauce. Obliterated

garlic. My mother

asked me to come home for the operation

to remove the sagging organ.

Agitated and uneaten

sugar dissolves in the innermost flesh. The apples

cider themselves. Brown fire

sizzling within each stinking fruit. Drunk

shadows suckled, hang from the telephone wire,

flapping off to squawk at other crooked shapes in the sky.

I roast a pumpkin whole in the oven. The glowing cavity. Collapsed light.

Jack o'lantern weeping juice from the touch of a knife.

I came home the night before the day

when she would splay

before another woman in scrubs. Soft

gathering of candle and scalpel bearers. These nurses

in surgical habits held vigil over

a sleeping body. Pulled the hollow gourd

from my mother’s earth.

My first home, dry rattling

wood shell. After the reverse birth

my mother beached on her side,

fluid filling her catheter bag. For seven nights

this sack outside her kept strange company. Hollow

and hallow be the Woman.

Echo chamber of many would-be babies.

Their impossible voices glance off the wet rock.

A cavern in sunset light, the red evening

of my mother’s changing. To be a woman

means to live partially underground.

Bloody as the beet root, the sacred heart

buried in the dirt.

That organ of wound and sugar, bleeding into

the mouth that moves it, chewing the dark earth.

As for me,

I cook dinner for my mother.

N: When has poetry failed you?

ZP: I originally came to poetry through the slam scene, starting off in high school, going to regional, state, and even national youth performances with the Taos High School Team. Then I left my hometown and attended university where I studied poetry through its movements in Western literature -- the early modern, the romantic, the contemporary. I have always been stuck between the stage and the page, wanting to milk language for all its intricate lyricism but also wanting to retain the immediate and embodied quality of performance poetry. So, to answer the question, it is not that poetry has failed me but that the existing forms in which poetry appears are not satisfying to me. I am constantly looking for ways to jailbreak poetry out of its relegated spaces.

N: Have you ever tried working in other art forms? Why was poetry the one to stick?

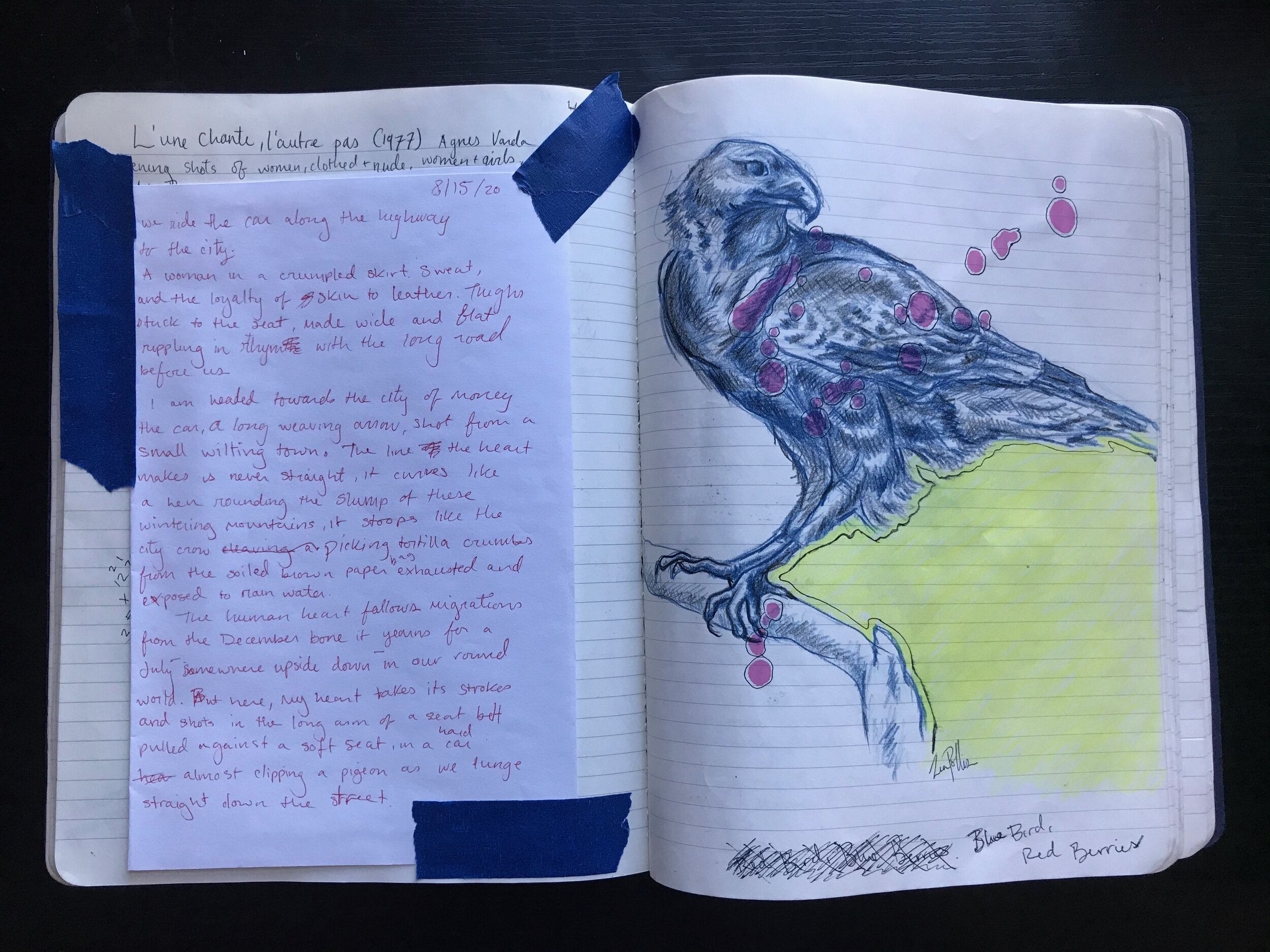

ZP: I am also a visual artist. The work I do is primarily illustrative realism with a surrealist bent, usually in colored pencil, pen, or acrylic. Poetry and visual art have always hung around each in my neighborhood, with me in the middle of their competing. attractions. My goal is to eventually combine them both in an illustrated chapbook or graphic (poetry) novel.

How to Eat a Woman

Like quince, that Edenic fruit, a woman

must be wet and boiled in a sugar brine of her own juices

else she is hard and tart and coats the tongue

with a dry chalk, the white stain, the acid ghost, bitter and discharged

from the garden.

Like mutton, a woman greys when left sitting, tepid at the table.

The ashen slit in the animal muscle, lavender and bruised with dead blood,

needs a sweet searing, pressed to the burning skillet

of the black iron bed. There she goes tender and weak to the touch, basted in butter

and the bite of her cumin.

Like mead, made from honey, a woman

is like a bottle beneath the dress. Her liquid weight sways with the swell

of elderflower and clover bloom and a handful of yeast

thrown like sand into the eyes of her drinkers. As if drowning, she bubbles in the mouth.

Let her breathe before tasting.

Feast beneath the rules of her table, else the food

never comes.

N: Would you give a single word prompt to write a poem?

ZP: Tenderness. This word represents something the human animal wants so much, yet we often harden when we encounter the cutting edge of events, other people, and ourselves. Tenderness is a three-syllable word with only Es for vowels. E is the most commonly used letter in English, so it makes sense to be in a word like tenderness which is so commonly needed.

N:Where can people find your poetry?

ZP: This is the first digital print appearance of my poetry. My nonfiction essay “The Wood Burning Prayer” has also been previously published in NAILED Magazine.

N: How can people support you?

ZP: I deeply appreciate the offer of support. My venmo is @Zia-Pollis. I am also starting an etsy shop for my visual art. You can find me at: etsy.com/shop/SunSpiritScribbles

The Poetry Closet is a semi-regular column of poetry and discussion, curated by Igor Brezhnev. You can reach Igor with inquiries, comments, and other messages pertaining to the closet at nailedpoetrycloset@gmail.com

Read the next Poetry Closet, here.

Zia Pollis is a poet and visual artist from Northern New Mexico now residing in Massachusetts. She holds a BA in English from Reed College and her nonfiction essay, “The Wood Burning Prayer,” has previously been featured in NAILED Magazine.