The Skin Underneath the Skin by Elle Nash

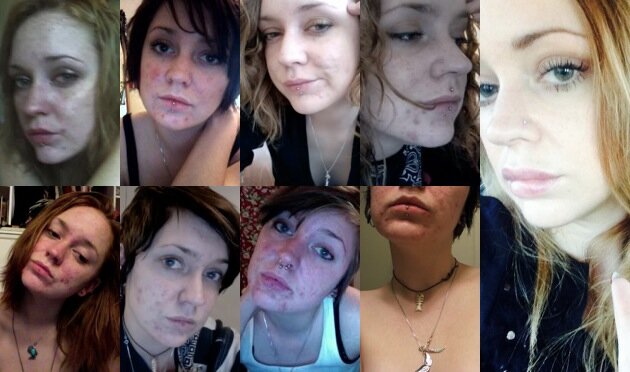

“what was going on while I was on this chemo-level drug”

+++

People think they see a person when they look at me but I am fake as shit.

My skin is the mask I manipulate so no one can see my insides. Papier-mâchéd with pore purifiers. Tightened with hot red lasers searing tiny holes into my skin, sucking collagen into the highest layer, wrapping around the deep scars from a decade of frantic picking. Acrylic nails glued to my hands so I don't scratch my skin off. Plastic permeable contacts in my eyes, black eyeliner, five layers of scented petroleum chemicals applied after every shower, every time I wash my face, medication to keep my skin from breaking out.

My skin, container of my body, betrayed me. I could not accept every dimple and curve the way body-lovers do, tracing their fingers over the stretchmarks of their own bodyhistory. Flaws were unforgivable. At fourteen years old I sat on my bedroom floor, cutting out pieces of models from magazines, cutting up pieces of my body. Tracing my fingers along their glossy magazine skin. I starved to make the sins stop, and when I could no longer starve, I puked. I had to repent.

I had zits on zits, castles of pus crying on each cheekbone, zits that stayed for months, painful bumps under the skin, bleeding, weeping. I stared at my reflection for hours. I’d clean my face with Dial soap, soak the bumps with scalding hot towels, use tea tree oil, toothpaste, scrub, I wasn't dirty, I wasn't dirty, it's under the skin it's dirty everyone knows and I can't get it out.

With my nails, my real nails, I’d press down on this inch-sized bump. When my skin was thin enough, the boundary between the outside world and my insides was thin enough to push the pus out, squirt it onto the mirror. My teenage mirror stained with pus. The bump would go concave, sucking into my cheek like an empty pit. It scabbed around the broken pore like a butthole.

All the ugly in me weeping out of my busted pores.

Acne vulgaris. My body’s sins.

Repentance is about guilt and shame and paying rent for your existence to your god. Penance meant pain. I had to reclaim my bodily autonomy somehow, and the only way to do that was to take it back violently and with force. A razor’s edge on my thighs, as if the blade that graced my legs would release me from the ground I stood on. My body. My blood. Everything back in my hands.

When I started throwing up my food and fasting, a purity happened. A cleanse. My skin cleared up and I was beautiful on the outside. Whatever was poisoning my skin, this boundary between me and the rest of the world, I could get it out of me. My body was mine. Nobody could hurt me the way I could hurt myself.

I reached double digit weights I will not repeat. There's a part of me that wants to brag. That wants to say, “double digits.” Wants you to sit on those two single digits holding up bones and a body dissolving in between them.

My first semester in college, double digits, weeping skin. Finals rolled around and I fasted for a whole week. I read books on Buddhist perspectives of desire. Studied for hours at Denny's, drinking coffee and Sweet-n-Low. No creamer. Water filled me.

By day three, hunger stops. Blood sugar levels out. Your teeth stop grinding for food.

The badges of anorectic honor: blue nail beds, feet you can't feel, not shitting for an entire week. It's been years since I’ve recovered, but I still get thrilled, turned on by a hunger so deep it doesn't register in the brain.

Seven days in. I eat a clementine to break the fast. A tiny orange, thin skin, an easy boundary to break.

Then I eat another one. And another. I open the fridge and grab mayonnaise and ketchup, hot dog buns, squirt the condiments into the buns and eat them whole without hot dogs. I make mayonnaise and ketchup sandwiches. Oreos dipped in peanut butter. Pop-tarts and buckets of KFC, mashed potatoes and gravy.

When I realize what I’m doing, I tell my parents I’m going upstairs to take a bath. I stick my fingers in my mouth, press down on the inside of my throat and I purge. All the transgressions, all the things that burst my skin open leave my body. The plumbing in my parents’ house doesn't work anymore. The toilet in the bathroom closest to my old bedroom is stained with dried-up water. The house pipes, fucked by two fingers.

The only way to make the binge-eating stop was to stop purging. You go good, you go so good for a long time, not eating too much. Losing weight and skin so clear. But it crashes back on you. The lizard brain overrides the will to die.

Eventually, things got easier because I got louder about my pain. Eating disorders are secrets. A safe little cave to fester. When I started telling everyone, it lost its power. I don't need to disappear, bit by bit, to show the world pain. I learned my triggers, tried not to act on them. I started running. Painting. Meditating. I stayed away from eating disorder memoirs and lost the online community I had before, girls on Livejournal liveblogging our deaths in symphony.

Once I moved out of my parents’ house, I stopped cutting, stopped throwing my food up. Mostly. My college roommate will tell you living with a person who is eating-disordered is hell. The fridge was a battleground. Protein on one shelf, produce on another, eggs on top. All the condiments neatly lined up in the door. I had to order the outside world to be aesthetically pleasing. I didn't need to focus on my body when my room was vacuumed twice a day.

The impulse wasn't at the surface anymore. I dieted here and there to control my outbreaks because sugar seemed to be the cause of my cystic acne. I faked health until I could no longer identify myself as a girl with anorexia. As a girl who pukes. I went insane trying to balance health and restriction without wanting to get to double digits all over again. You can have nice skin and go fucking crazy, or you can break out like the wormbaby you used to be, eating bread and rice and all the shit normal people eat.

I chose bread.

When I got a big girl job and started making money, I went to a dermatologist. I lied and told the dermatologist that I'd been on every antibiotic possible, that nothing worked. I had heard of this drug called Accutane that would clear your skin up like a movie star. Erase the scars and bumps like the past had never existed, like I’d always been pretty on the skin.

By law, doctors are supposed to try every single option for acne before they prescribe Accutane. By law, patients have to be on two forms of birth control for the entire period they take it, because Accutane causes birth defects. And by law, you have to take pregnancy tests at the doctor's office once a month to prove you aren't lying.

Accutane was the first medication she prescribed to me.

I was tired of low-carb low-sugar low-life shitty diets. I was ready to accept anything it took to get rid of my acne.

Accutane is the only non-psychotropic drug with a black box label for suicide. In 2002 a congressional oversight committee released an investigation that found at least 200 people had taken their lives while on Accutane since the drug was released in 1982.

I figured 200 people out of whatever was good odds.

On Accutane, all your nightmares come to surface. Every zit you've ever popped. Castles filled with pus. Whiteheads. The purge can happen for three to five months. Your skin sheds abnormally fast and a shiny new you is underneath. Like a lizard.

Your skin gets paper thin and dry. You get addicted to chapstick. I bought a tub of vaseline and carried it with me. I hid it at first, hoping no one would notice, but my lips were so drughouse dry I whipped it out everywhere. Dinners. The movies. Office meetings. My skin snowed. Think that mousey girl from The Breakfast Club. Face dandruff on my pillows, couch, bed sheets, my black clothes. The boundary between myself and the outer world dissolving. You forget you were ever a certain way before this. You forget that you’re not always shedding, disappearing. Bit by bit, into dust.

My joints hurt and I couldn't run anymore. I was running 6-7 miles on a regular basis and breaking my knees. Even now, a year after being off Accutane, I can barely run a mile. When I could no longer run, the snap impulse to hurt would come back. Anything could go wrong; I’d say something wrong, forget a task I had to do and my first thought was to off myself.

The itch grew. My skin was so thin I’d find scratches all over me. I stopped wearing makeup and stopped using mirrors, slept twelve hours a night. This time I cut on my ribs. Tiny shark gills on each side to allow me to breathe out and keep moving.

To stop cutting, I started smoking. Starving turned the dial down on the intensity. I rationalized these self-destructive behaviors to keep living while I was on that drug. If I didn’t hurt myself now, I would hurt myself worse.

Sick how it felt like home after all those years. The corners I crawled into in my bathroom, grasping at the sink and crying. Fluorescent light in my eyes. The Exacto knife. You grab a piece of skin on your ribs and hold it tight, take the knife and move the blade between the bones. And because you don’t want to die, you do it again. The blood is warm. You look at the open wounds in the mirror and try to get closer so you can see what’s opened up underneath, all the pretty parts of you spilling out onto the tile.

There you are, in the skin underneath the skin.

I knew whatever pain was going on was temporary and I allowed myself the starving, the cutting. The way junkies rationalize the last hit before quitting.

Internal FDA documents suggest the initial number of 200 suicides uncovered by congress was less than 1 percent of the total. More likely it’s in the tens of thousands.

I came off Accutane in November last year. My skin is mostly clear. I want to say that what was going on while I was on this chemo-level drug was not me, but I can’t. The past is still a part of you. No one gets to see that world unfolding in me unless I let them. I still control the boundary, but now I embrace it. Skin and all. All that penance I was paying to god was penance paid to me. I’m the god. And I don't want to apologize for myself anymore, because I am alive. I’ve fucking made it.

+ + +

Elle Nash is a writer in Denver, Colorado with her fiance and her cat. She had the opportunity to attend Tom Spanbauer's Dangerous Writing workshop in 2013, and has dreamed of Portland since. Her work can be found at Exterminating Angel Press, Blue Skirt Productions, and 303 Magazine. Sometimes she blogs, here.