Response: Cheating

“before I pulled up my big girl panties and broke up with my current partner”

In our monthly Response Column, NAILED asks readers to respond to a particular word or topic. We seek to publish raw, honest personal responses that aim less to answer questions and more to raise them. Responses come in the form of art, photography, essay, story, poem, and rant. Read all of the previous Response columns: here.

+ + +

Response: Cheating

The Great Expectations Artists, by Jason Arias

A halfie, a midget, and an Italian walk into a music store. It sounds like a bad joke. Maybe it’s a riddle. They each have at least two other names. The halfie goes by Jason and Oreo. The midget goes by Sean and Stubs. The Italian goes by Tony and WOP. I’m the halfie. Half Dominican, half whatever.

There’s no political correctness among us. It’s pre-PC here. None of us has a desktop at home. The Internet doesn’t exist. We’re just three kids using the ugliest parts of our histories to destroy any future expectations anybody may have for us. We have infinite identities and infinite disregard and an insatiable hunger for Bay Area music. Digital Underground. Too $hort. Hieroglyphics. Tupac. Oakland-based music keeps our Portland heads bobbing.

We enter the music store that’s in the Fred Meyer’s that’s in the heart of Rockwood. We each enter at different times. We’re not friends here. We’re just three separate music consumers that, together, make a joke with no resolve; a riddle with no purpose. We’re more like an illusion. More like a magic trick.

I go in first and head to the Jazz section in the far left corner, nod to the thirty-something clerk as I walk by, hold my pants up at the crotch so they don’t slide right off my ass.

Sean’s next, minutes later. He goes straight to the Rap section towards the middle of the store and starts flipping through tapes behind the plastic ‘T’ tab with his small, chubby fingers. Those fingers are the reason we call him Stubs. I think they’re the reason he’s always trying to prove himself to us. But those fingers and his stature are also the reason that the thirty-something clerk immediately looks away when Sean catches him staring. He looks away and doesn’t look back. I’m not really needed as a distraction, but I’m here to give the clerk a justifiable alternative.

I’m still in the Jazz section justifying: looking back constantly, turning the tapes over and over in my hands, readjusting my pants. It’s a backwards flirtation dance between me and the clerk: eye contact with quick-cuts to the right and left, ambiguous lip contortions, incessant crotch grabs. Him in pleated khakis. Me in ironed jeans. Both of us at work, in different ways.

Just before the thirty-something clerk goes for the phone Tony enters in a pair of Levi pants that actually fit, a Gap tag self-sewed to the back pocket.

He says, “I just need a player with the right balance of bass boost, sir.” He points to a Walkman on the half-wall behind thirty-something. “What about that one?” he says.

I don’t even need to look to know that this is the moment that Too $hort and Tupac start disappearing up Sean’s sleeves and into the sides of his coat lining. He’s not just a thief, he’s a magician, he’s an artist. His clothes are riddled with invisible pockets and hidden slits. Anything about the size of a cigarette pack or tape case are Bermuda Triangle-d with his smoothness.

By the time thirty-something turns around to hand the Walkman to Tony, Sean’s disappeared what was in his vicinity, onto his person and starts walking. Just like that. Smooth.

But behind thirty-something’s head I see security walking toward the music entrance, just one overweight guy in one of those puffy, black, cop jackets. Maybe they got cameras in here between the last time and now. Maybe thirty-something just pushed a button somewhere. Maybe this is why magicians don’t perform the same trick too many times in the same city.

Sean and the security guy meet at the entrance/exit—just one gaping opening with grocery checkout stands on the other side. Security’s looking down at Sean. I don’t recognize him. He’s definitely not the same security that picked Sean completely up off the ground by his collar last week at the Tower Records at Gateway, when Sean yelled, “You’re not my daddy!” and the guy dropped him looking all stunned, and Sean got away because Sean knows how to think quick. But maybe this security knows that security somehow.

I think I see Sean panic for just a second. It’s just a little shiver, just a tiny tic. Then he bares the most innocent, freckle-faced smile; his sandy hair poking out the sides of his ball cap.

Security opens his mouth and says something and nods friendly at him. Security turns, nods at thirty-something. Thirty-something turns, nods towards me.

When I can’t see the back of Sean’s jean jacket anymore I start nodding to myself.

I hear Tony say, “That’s not going to be enough bass, man,” at the counter.

Security walks to the Jazz section, looks down at me, and says, “You got a problem with your pants, son?”

A halfie, a midget, and a WOP enter a music store and come out a mulatto, a little person, and an Italian. They come out a blasphemy, a half-pint, and a Guido. They come out a probably, a maybe, and an unknown. They come out with so many cuffed doves and flying card tricks that people start believing what they’re showing them. They take turns putting themselves in boxes, then cutting the boxes in half, then cutting the halves again. They keep cutting ‘til there’s nothing left but sawdust and hand tools. And the audience is invited onto the stage to sift through the remains saying, “Here’s proof of this and this and this.” But there’s never proof. There’s only deception and flair. There’s only the dust of expectation and deception flying around them.

And then the wind picks up.

And, poof!

Just like that, Tupac’s playing on the tape deck.

+

Jason Arias lives in Portland, OR with his wife and two sons. Many of his cassette tapes were lost long ago. Some of his previous writing can be found at Blue Skirt Productions, Nailed, the Nashville Review, Perceptions Magazine, and the new anthology (AFTER)life: Poems and Stories of the Dead.

+ + +

Bartenders Steal Your Money, by Colin Farstad

It goes like this: you order a drink—hopefully not obnoxiously by asking what’s good or saying something like just make me something good and if you do ask for advice, at least know what liquor you like to drink because here’s the thing that somehow you sometimes manage to forget: you won’t like every drink a bartender can make—but no matter how you get there, once that drink is ordered, you’re given a price, hopefully it’s cheap because I live in New York now, not Portland, and sometimes you end up at one of these places in New York where the drink is most definitely not cheap, I’m talking ten-dollar-shitty-pour-well drinks, but I work in publishing so I always avoid places like that, but when you pay for that drink, and you pay in cash, sometimes, every now and again—the delicate balance of the ecosystem is they can’t do it all the time unless they’re the kind of truly horrible person that does do it all the time—that cash does not all end up in the register. Sure, you’ll see them put it in and make change and make sure you’re going to tip them too, but I’ve seen it all: no sale so that the drawer opens but nothing got rung up, charging for a two dollar bottle of High Life instead of your thirteen dollar artisanal, shaved ice, stirred for thirty seconds, at least, two special kind of bitters that the bar makes themselves, because whether it’s Portland or Brooklyn, you can always find places like that these days, and only one of the cities has a show where they make fun of it. However it gets done, that extra cash goes into their tips. The truth of it all is though, it’s easier if you order the drink and then walk away because they don’t have to go through all the pantomime show of putting it in the register.

But it’s not just outright theft all the time either. The bartenders that cheat and steal the most are your friends. You start a tab, without a card because they know you, they went to your college as an English major too, and your bill at the end of the night is four, maybe five drinks less than you and your friends ordered, and the bartenders know, and you know (or you should), that by not charging you for those drinks, you have entered into an agreement where you must tip them proportionally to the amount they gave you for free. It is still stealing, it is still theft, but you know, they know, the bar knows, the manager knows, this whole three hundred percent mark up on booze, charging six dollars a shot for something that costs the bar six dollars for the whole bottle is a racket and your college degree, that fancy piece of paper you don’t remember where you stored away during your last move, costs way more than that and that theft is paying off the student loan debt the bartenders carry up the hill every month.

+

Colin Farstad's work has most recently appeared in Split Inifnitive, Analekta Anthology and Coal City Review. Colin has been a teacher, editor, writer and event coordinator. He currently lives and works in New York City.

+ + +

+

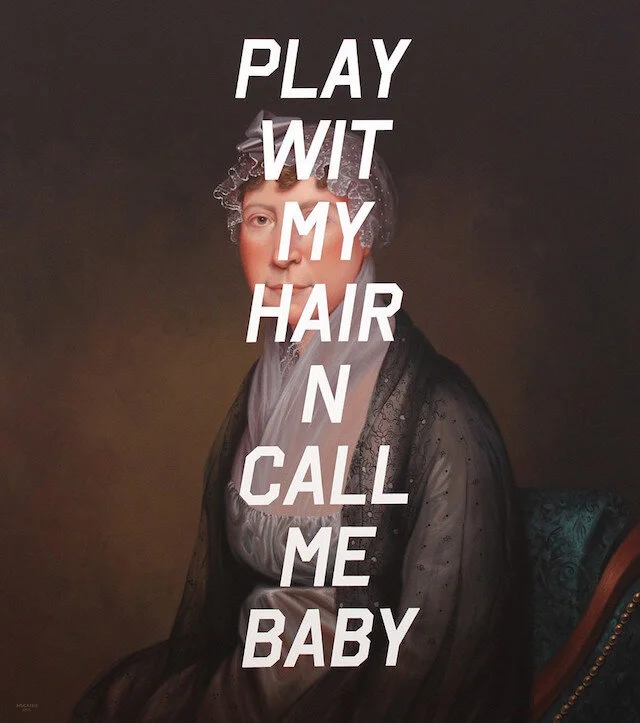

Shawn Huckins (1984) was first introduced to painting after inheriting his grandmother’s oil painting set at a young age. As an adult, it’s taken a route through studies in architecture and film, plus a stint living on the other side of the world, for him to gravitate back towards art. Since graduating from Keene State with a major in Studio Arts, Huckins has taken inspiration from 18th Century American portraiture to 20th Century Pop Artists and preoccupied his work with a contemporary discourse on American culture. He currently lives and works in Denver, CO.

To view his Artist Feature for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

Cheating, by Kristen Mackenzie

Am I cheating?

When I spin out on the corners in the wintertime just to make my heart go faster, when I go hiking alone, or indulge my love of bacon? If I kissed a woman while I was married to see if I was gay? (I am.)

To those, I can confess (and one other I won’t mention for fear of audit).

But watch me and I’ll hide the things that matter. Maybe you won’t see because you do the same.

Another hour on the computer instead of a trip to the gym.

The story I almost wrote but didn’t.

A woman on the ferry so right for me it made my heart stop but who I watched drive away without saying hello.

I cheat myself.

+

Kristen MacKenzie lives on Vashon Island in a quiet cabin where the shelves are filled with herbs for medicine-making, the floor is open for dancing, and the table faces the ocean, waiting for a writer to pick up the pen. Her work has appeared in Brevity, Rawboned, GALA, Extract(s) Daily Dose of Lit, Maudlin House, Blank Fiction, Cease, Cows; Crack the Spine, Eckleburg, Referential, Bluestockings, NAILED, Knee-Jerk, and Wilderness House and is included monthly in Diversity Rules. Pieces are forthcoming in Minerva Rising, MadHat Annual, Mondegreen, Prick of the Spindle, and Crab Fat. Her short story, "Cold Comfort," placed in Honorable Mention in The Women's National Book Association's annual writing contest.

+ + +

+

Matteo Nazzari, born in Venice in 1977, holds a degree in Cultural Heritage to Archeology from the University Ca ‘Foscari of Venice and also attended the Roman School of Photography. He has had several solo and group exhibitions in Rome, Bologna, Paris, Barcelona, among others. He currently lives and works as a freelance photographer in Milan.

To view “When No One's Looking,” his photo essay for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

(Good) Grief, by Paul Crenshaw

Lucy holds the football after assuring Charlie Brown she won’t move it. She smiles up at him and Charlie chocks himself, prepares to hurl his momentum forward. And though we all know she will yank the ball away, have seen it happen more times than we care to count, it is in this moment we feel the hope of possibility, like a lover’s sweet scent or an infant’s fine hair. We hold our breath as we strain toward the screen. We are always swimming with want: our lives to grow long, our children to grow tall, our parents to never die. We create shapes in the clouds as if we would bend the weather to our will. We hold onto the hard spin of the earth, center ourselves by staring at the stars. We want the assurance of sunrise, the hope of the hurricane’s eye. We wish for what we have and want what we’ve thrown away. We are struck by memories so hard they hurt: the dog that dragged itself off to die or the day our daughters were born. Our mother’s warm hand on our foreheads, her voice soothing away the sobs. Our father’s unshaven face scraping our thin skin one winter morning as he leaves for work. Our grandmother cooks in the kitchen while our children play in the yard, her slow stirring forcing us to face how finite we are.

With each choice we make to love, there is the chance of loss. The lover leaves, the child moves out, the parents pass away. We will be betrayed by time and tide. Cheated again or cheat. We hurt, and we hurt in turn. But we keep coming back to this cause, keep flinging ourselves forward against the chains that bind us because they also hold us together. We bear the past into the present with all the longing of love and sound of song we can carry, and though we fear the things in the future that have already happened, we hold onto this moment and hope with the speed of Charlie Brown running toward the ball. Lucy’s finger pins it to the Earth like the gravity that holds us all here.

Just this once, we say.

+

Paul Crenshaw’s stories and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in Best American Essays, Best American Nonrequired Reading, anthologies by W.W. Norton and Houghton Mifflin, Glimmer Train, Ecotone, North American Review, and Brevity, among others. He teaches writing and literature at Elon University.

+ + +

Almost 20 Acres: Excerpt from a novel in progress, by Davis Slater

Smoky Gray was a backwoods entrepreneur always looking for his niche market. By his fortieth birthday, he’d bankrupted businesses selling hot tubs, satellite dishes, exotic pets, some kind of high-tech tin foil that went over your insulation, and patented pick-me-up-slash-diet pills that ended up being pretty much just speed. He’d hustled sunglasses, moonshine, fishing lures, and knock-off perfumes. In bright sunlight, you could see the stick-on letter ghosts of five company names on his van doors. His third wife Barb said of his latest bankruptcy-to-be that at least it had some bought-and-paid-for land to it, so they wouldn’t have to live in the van when the bank took everything else. Smoky’s enthusiasm was undimmed.

He’d tripped into the land, seeing a public notice of a sealed-bid auction for a schoolhouse and grounds the county had replaced a couple decades earlier. After he’d paid his fine for posting makeup ads beside the highway without a license, he got to chatting with courthouse secretary Jonelle Shaleen, a woman who was so fucking done with this day she didn’t care who knew it.

Jonelle said the deadline for the sealed-bid auction was close-of-business that day, and, as expected, they hadn’t had any bids yet. “The big real estate companies always wait until the last minute. They’ll have ten bids here at four-twenty-nine, and I’ll have to stamp every one received, log it in my book, and fill out a form for each one before I get to go home. Assholes.”

Smoky had liked the look of Jonelle: fancy work clothes, plenty of makeup, and shiny, dangly earrings that looked like one of the popular fishing spoons he had sold years before, so he kept her talking for a while. She said the property was pretty run-down, since they hadn’t allocated any money to mowing in years. “It’s almost twenty acres. I don’t know how blessed many football fields they thought they were going to put out there.”

Smoky said, “It’s a shame they make you stay late for those real estate companies. You should tell ‘em to shove it up their ass.”

She said, “You ain’t lyin’. The way my day’s goin’, I’m damned tempted.”

Smoky knew he had ten dollars and four quarters in his pocket and no prospects of getting any more.

He produced a ten-dollar bill from his pocket and handed it to Jonelle. Told her, “Why don’t you close up shop and take me out for a beer with that?”

She smiled crooked, talking herself into it. She looked at the clock. Four fifteen. Nobody else around. She nodded. Snatched her vinyl typewriter cover off the floor and started to fit it over her Selectric. Smoky said, “Hang on a sec.”

He swiped a piece of typing paper and an envelope from Jonelle’s desk, wrote his name and address and the notice number, wrote “one American dollar,” and sealed the paper in the envelope. Said, “Could you just stamp that for me first and log it in your book?”

+

Davis Slater's fiction has appeared in The Masters Review, The Dead Mule School of Southern Literature, The Gravity of the Thing, and elsewhere. His story "Know My Name" appeared in NAILED.

+ + +

+

Theo Gosselin was born near Le Havre in Normandy in 1990. He grew up with the sea, the wind, the forest, and the sound of electric guitars, echoing in the deserted streets of this grey city from the north of France. He started photography around 2007, and it became his reason to live. His photography reveals friends in the act of escaping from their regular lives into newly enticing and perilous modes of existence, ever in search of the persistent though elusive idea of freedom.

To view “Vagabonds,” his photo essay for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

Aftermath, by Sarah Michelle Sherman

It was a Sunday afternoon in April and I was working my normal bar shift at a small pub in Albany when my brother walked through the door looking defeated, broken—a look he didn’t wear often, or well. I didn’t know he was coming, and it wasn’t like him to visit unexpectedly. He made his way toward a bar stool and took a seat. He placed his red, poorly circulated hands on the bar and began picking at his cuticles—something we both do when we’re stressed. He looked at me, shook his head.

That’s when I knew.

Tears formed in his eyes and my stomach went hollow. They looked as if they were filling with wax. Tears so thick, they looked as if they could seal his blue eyes completely shut. Tears so thick, I wondered how he could even blink.

“I’ll take a Guinness and a shot of Jameson,” he said.

I nodded, and then turned around to grab the whiskey and two shot glasses.

We clinked glasses. No toast. No cheers. We threw the liquor back, then I just waited. Waited until I knew what to say, waited until he did. He cracked his knuckles as he slowly pushed out the words that must have burned like acid in his throat.

“My marriage is over.”

All I managed to say was, “I’m so sorry.”

He choked back his beer as he told me about her affair. He told me how His wife and her lover would leave school in the middle of the day, when they didn’t have students, and fuck in the parking lot. And how once she had asked him to take out the car seats so she could have the car cleaned, but really it was just so she’d have room to mess around. And how she was late to their son’s birthday party because she was with the guy she’d later call her “soul mate.” And how she’d text that scumbag while sitting on the couch directly across from my brother.

I couldn’t hide the disgust on my face.

“I hate her,” he said.

“I hate her, too.”

I tried to stay strong, knowing it was what he needed from me, but it was a role I never played. I told him clichéd things, like, “you deserve so much better,” and “you’re better off without her.” He told me his main worry was the kids. Then he asked me to swear on our grandmother’s life that I wouldn’t tell our Mom or Dad.

“Mom has too much going on,” he said, and I promised not to tell.

That Sunday, I ignored the other customers at the bar. They could wait; my brother couldn’t. Most of them were regulars and when they waited a few extra minutes for their cocktails, I apologized as I nodded toward the broken man and said, “Sorry. That’s my big brother,” and I told myself they understood.

After a while, he asked, again, for another Guinness, a shot of Jameson, and reassurance that I’d keep our first secret. I told him I would. And I meant it.

+

About a month later, the two of them had already separated and were splitting time with the kids. I went over to my brother’s house on a Saturday and four-year-old Natalie rushed toward me as I walked through the door.

“Auntie Sarah! Want to play?”

I offered her my hand, let her lead the way. She guided me upstairs to her pink bedroom, her walls covered with dragonflies, owls, a porcupine. I followed her over to her easel and watched as she pulled out markers, crayons. I did as I was told—drew a kite and an elephant. And another. And another. She copied what I did. I thanked her when she told me I did a good job. I envied this innocence, fooled myself into thinking she didn’t know what was going on, but quickly found I was wrong.

After maybe ten minutes of drawing, she set down her blizzard blue crayon, paused, tilted her small head to the left, and stared at our work. Her old soul seemed to flood the room as she sighed with apple juice breath. She looked at me with sad eyes and quietly asked, “Will you draw me one more thing?”

“What’s that?”

“A house where my mommy and daddy both live.”

I paused and hoped her mind would go somewhere else. As she waited for my answer, she grabbed my braid, asked me to make her hair look like mine. Instantly relieved, I smiled, told her I loved her.

+

Sarah Michelle Sherman recently graduated from The College of Saint Rose in Albany, NY, with her MFA in creative writing. While studying at Saint Rose, Sarah worked as managing editor of Pine Hills Review, the college’s literary magazine. Now, she is an adjunct professor at her alma mater. For three years, Sarah has worked as a freelance writer and columnist for Albany’s alternative newspaper, Metroland. Her writing has also previously appeared in NAILED, as well as Thought Catalog, and Ploughshares Online. Find her online: here.

+ + +

+

Kaethe Butcher is an emerging 24-year-old artist and illustrator from Germany. She is heavily influenced by Egon Schiele and Art Nouveau.

To view her Artist Feature for NAILED, go here.

+ + +

How (Not) to Cheat, by Lavinia Ludlow

I’ve cheated on exactly 40% of my partners. Depending on how well you know or think/assume you know me, that could be a shitload or a few minor transgressions.

Although I’ve never thought about cheating as wrong or something that would send me to eternal damnation in my own agonistic hell, I fully recognized that my decisive actions were hurting someone and forever changing our course of intimacy, whether or not he ever found out. They say sobriety starts (and restarts) on day 1, meaning there are a shitload of times you can hit the reset button before you really start pissing people off and testing their faith, but faith in monogamy is shattered on day 1.

There was never any common reason why I strayed either, sometimes it was boredom, revenge, or I wanted to be with someone else before I pulled up my big girl panties and broke up with my current partner. In conversations with friends, family, and fleeting acquaintances, I’ve found that their dissatisfaction with their partners was directly correlated with their entitlement or drive to cheat.

He/she neglected and drove me into the bed of another person.

He/she always chose his/her friends/mother/ex-husband/ex-wife/kid(s) over me.

He/she did it first.

He/she was an asshole.

He/she was just too different from me.

I can identify with all of these since the degree at which a partner was incompatible with (or an asshole to) me was directly correlated to how guilty I didn’t feel when I cheated on him. I am also human, and it’s human nature to take any internal dissonance and spread it thin over a massive rationalization until it vanishes. However, I’m honest enough to know that fucking around has never been accidental or unplanned. Every time I did it, even in the rock bottom throes of esteem, sobriety, and life, yes, even on the brink of suicide, I knew exactly what I was doing.

I’ve also never cheated to accomplish something, and I adamantly refuse to believe the act is a debatable moral dilemma. Ashley Madison’s CEO said, “The majority of people who have an affair use it as a marriage preservation device.” To me, this is comparing infidelity to stealing bread to feed a starving child. Steal or starve. Cheat or break up. Fucking around behind a monogamous partner’s back is a fucked up shitty thing to do and it makes people feel like shit.

Naturally, I haven’t been without a fair share of unfaithful partners (I wouldn’t be surprised if there were more that I never knew about), and discovering it was never an earth-shattering, life-destroying revelation that plagued me with intimacy issues (life’s done that on its own). As I got older, being cheated on is something I understood that came with the territory—dine out at gas station coffee shops enough, and you’re going to eventually find a bug, Band-Aid, or fingernail in your food.

But I have recently been hurt. Bad.

And this wasn’t a, “I accidentally pumped my dick in and out of a rando last night, and I only came once and it was weak because I was drunk and she was fugly” scenario. This endearingly short, imperfect but authentic, whip-smart-ass who could serve me a helping of tough criticism with a dollop of tenderness, and is still the only person I’d ever wanted to serve and be served by, to colonize and be colonized by, whose arms I could lie in forever, helpless, smitten, and stripped of my sharp edges and bitterness, revealed that he had been cheating on me. With his wife. With whom he had a three-year-old son.

Oh yeah, that was a three hundred and sixty degree sucker punch. I felt the foundation and structural skeleton of my new life annihilated as if a demolition team had spent the last year laying dynamite that would cut me to my knees and leave me a pathetic pile of “other woman” rubble in a foreign country. In that moment, everything about us ceased to exist. The conversations we had, the promises we made, the sheets we soiled, were utterly fraudulent.

When I was ready to talk about it, a friend tried comforting me with, “We’re not meant to be monogamous, especially guys. Maybe we should all be polyamorous.” She, however, believed polyamory was just another way of saying open relationship. As I understand polyamory, multiple people enter a commitment to each other, which doubles (or triples) the chances of hurting someone or getting hurt, not to mention dealing with the exponential rise in modern relationship complexity and drama. “How many times do I have to repeat that I have a headache tonight? Which one of you fuckers left the toilet seat up? You’re all sleeping on the couch!” Or worse, I’m on the couch while the rest of them are canoodling in the bedroom without me.

I’d like to be able to pass on my lessons learned like, “what goes around, comes around” ; “don’t be a (man)whore” ; “don’t get too comfortable” ; “forgive and forget” ; “nothing lasts forever” ; “no relationship is perfect,” or “life’s going to fuck you one way other another, whether cancer, lawsuit, or infidelity,” but I have nothing. The only understanding I carry forward is that I once wholly and unapologetically devoted myself to someone, and I had negative desire to stray. During that finite amount of time, I became the best version of myself, and therefore, the best partner I would ever be for someone. That’s the best any of us can do for ourselves, and the most we can hope to find in another.

+

Lavinia Ludow is a musician and writer. Her debut novel, alt.punk, is available through Casperian Books, and on March 1st, 2016, the indie publisher will release her sophomore novel, Single Stroke Seven. Her short short fiction has been published in Pear Noir!, Curbside Splendor Semi-Annual Journal, and The Molotov Cocktail. Her critical reviews of indie lit have appeared in Small Press Reviews, The Collagist, The Nervous Breakdown, Entropy Magazine, and American Book Review. When not traveling for work, Lavinia divides her time between San Francisco and London. Find her here.

+ + +

Header image courtesy of Karim Hamid. To view a gallery of his art on NAILED, go here.