Life Model by Laura Green

“Today I stay naked while they talk. Get more naked. Bra off. Whatever.”

+++

This is a work-study job.

“I think it’s telling that more than half of you drew her scar.”

The studio is warm. Most of the others are freezing all fall and winter. Freezing late into spring -- the sculpture studio, for example, down by the stream. But this one, in the attic of Ely Hall, is brick and granite, thermal as a snake.

“Isn’t it interesting? What do you guys think?”

It has skylights, huge skylights and today is sunny and no snow on the roof. Three bright rectangles heat up the wood floor. Three rectangles each one as big as a room. Easels and chairs covered in paint, backpacks, winter coats slumped in heaps interrupt the light, catch it, cast shadows. Everyone -- every stool, every piece of newsprint -- wants it to fall just on them, which is fine with the sun. Take what you want. Heat? Take heat. Brightness? Take brightness, then.

“I mean, it’s not that big, really.”

All the drawings are lined up on the floor, propped against a wall. All the students face the wall, away from me -- sleek head, shaved head, blond dread locks, wool cap. A green army jacket, a purple scarf. They shift, most wrap their bodies in their arms. None speak.

There’s something brilliant about the purple scarf — something beyond me.

“Look -- it’s here, and here.”

The teacher walks forward to tap my scar on the paper of their pads -- a smudge of black, one sharp line of gray. The air smells like oil paint and pencil shavings. If you close your eyes — pine forest and second grade.

If you close your eyes while they’re at work someone will say, open your eyes, please? (Not Scarf Boy. Someone else.) Your face in their picture is a thumbprint blur, but they know your eyes were open.

“It was a quick study -- impressions. So…what do you think, class?”

Some people bring robes to wear while they discuss - I just pull my shirt back on. Or sometimes I don’t bother. It seems strange to cover up when they’ve stopped looking at me. When they’re looking at me filtered through them onto paper or canvas. But then, maybe it’s strange to be naked when I don’t have to be. Maybe they’ll realize something about what I want, what I’m getting out of this. Something true and unbearable. Something I don’t even know myself.

It’s sketches today, which is easy. I hold a shape for five minutes, maybe three, then a different shape. Lately this teacher has me pose with my clothes part way off or, I guess, part way on. This time everything off but my bra, arms back to catch its clasp.

Clasp it? Unclasp it? Since I’m still, there’s no difference. Or maybe there is.

“It’s important to think about the images you’re making.”

On, I think. I think I was putting it on.

Today I stay naked while they talk. Get more naked. Bra off. Whatever. The light falls all over me, but not because I want it to. Not because I’ve claimed a spot in it. I stay on the platform where the teacher put me and, today, I’m warm.

This is a work-study job.

“Here it is — and here, in Nathalie’s, Sam’s. Why, do you think? Does anyone have a thought about that?”

Plenty of students have work-study jobs.

Plenty don’t.

A boy named Elm and I compete sometimes for being most poor. His parents raised him in a cabin in the Adirondacks. They ate squirrels. My elementary school babysitter freebased cocaine at her kitchen table while I read to her children in the living room. The disadvantage is shallow, though, for both of us. My mom got passes from the library and took me to the Museum of Science every Saturday. The Children’s museum on Wednesdays. Sundays the MFA. Elm’s parents taught him to recite Leaves of Grass from memory. They named him Elm.

And here we are at Vassar.

“Think about it. Come on.”

Elm is best friends with a boy I’m fucking - Joseph. I’m fucking Joseph because my best friend Amy said he was cute. Like a prince, she said. Look at his curls -- he’s basically a boy king. Amy doesn’t have a work-study job. Neither does Joseph.

The students all seem perfect, from behind. If they were naked and I was drawing I’d draw them confident and sure. College Students. If they had scars I’d draw their scars but in a way that made them seem more whole, not broke open. If they didn’t have scars I’d draw their loose shoulders. I’d draw their soft necks.

Flecks of charcoal dust float through the air. The specks are black but they catch the sun and light up. For now they’re specks of sun. They float and spin. Eventually they’ll have to settle to the ground, but not yet.

“Come on, people.”

The teacher stands at the end of the row of drawings. He leans against the wall, like he’s the final picture. The one everyone wishes they’d made. He’s frustrated with them, but not with me. I don’t have to wish I’d thought to focus on this instead of on that. I’m not responsible for the answer to his question. I’m his question.

“Maybe the angle we were looking at her from? From which, we were looking — like, maybe some of us couldn’t really see it.”

A boy in a Pabst Blue Ribbon trucker cap. Red foam in front, blue net in back. Straight brown hair all greasy in his eyes. At home that hat on this boy would make me feel cautious. Worried about the fathers he’d gone through, the shape of them, how they taught him to grow. I’d worry about what shapes he saw in me. But here, it’s different.

“No, no because…look where it would be in your drawing. See? It would be right there, but it’s not. Not because you didn’t see it -- but you didn’t grab on to it. Why? Why could that be?”

In his drawing there’s no black slash. In his drawing my stomach is just light.

Last night, without the sun, it was cold here. It always is at night. They bring in space heaters for Open Studio but the rattly metal boxes with their dutiful fans, embarrassing cords, can’t hope to compete with the great, dark sky overhead.

At night there’s no teacher and no discussion, I sit completely still for twenty minutes and take a break. Sit still for twenty minutes and take a break. Sit still for twenty minutes. I almost always sit -- it’s easier. The students can’t tell me how to pose - they’re just students, like me. I’m in charge of myself which almost makes me in charge of them.

Ahhh, could you look back at what you were before? No but, like, your eyes? It’s just, you moved. Your gaze. Is. Different.

Once I’ve made my choice, they can hold me to it.

There’s prop furniture stacked here and there, a round table painted black, carved spindle legs. Black plastic chairs that glint rainbows. A pink armchair upholstered in something that’s unraveling. I gather the brave heaters, turn them so their orange coils glow at the chair’s feet. The florescent lights rattle and hiss above us. I curl in the scratchy pink chair.

At night the main doors are locked. To get in we climb metal stairs that cling their way up the brick wall of Ely Hall with brackets and bolts to a landing made of wire mesh, high above the winter-dead grass. Last night Amy came along. She sat in a black rainbow chair and wrote. She watched the art students look at me. You can make the scene if you want, I offered Amy on our climb up. I’ll pose however you say. If you want.

After, we went back to our dorm -- to the bathroom that has a tub. It’s on the fifth floor, which is where the girls’ maids lived back before. When the girls were ladies and their maids were girls. Claw foot, left over. Too heavy to bother with, maybe. All those flights of stairs. They built a stall for it, a tiny room inside the big bathroom. It filled with steam in seconds.

Amy rolled up her pant legs and perched on the tub’s curled lip, notebook on her knees. It’s taken months for her to let me see her feet. Hands and wrists, some arm, feet and ankles, a little leg. And her face. Her throat. That’s what I’ve seen of Amy’s skin. I took off my shirt, again. I took off my jeans. Unclasped my bra and slid in. She said, Okay, lie on your side. She’ll read me her stories but only if I don’t look. Even when I’m naked, even after I’ve been naked. Turn. She pressed her cold toes against my hip.

“Um, is it, maybe, because we’re like, looking at the surface?”

A girl named Tammy feels unsure but dares to venture. All the students love this teacher. Maybe because of his body which is like a spring. Something coiled and self-charging. There’s rumors he has AIDS. HIV, I guess. He’s all thick flesh and life. They love him so much they can’t speak. Or they love him so much they talk loud and non-stop. There’s rumors he has a beautiful boyfriend who used to be his student. Tammy drew my scar. Was she looking at my surface?

“Well, you’re drawing her so you have to look at the surface Tammy, but good idea. Why that surface? Why do you think that’s the thing you saw?”

Every single sketch looks different from the next. Not one of them looks like me. Or at least not how I look filtered through my eyes onto my brain. Scar, no scar, scar, scar, no scar… I mean, it’s not that small, really. Wider than the span of my hand. From my hipbone nearly to my belly button. Is it telling that almost half of them didn’t draw my scar? Why isn’t that telling?

Tammy tries again.

“Maybe is it something about, like, imperfection? Like the thing that’s wrong…?”

I’ve slept with all the boys Amy says are cute. I don’t know why, exactly. I think it makes me stronger, for her. Somehow it makes me more heroic. The boys she wants want me. That makes me more the person she would want.

I’ve slept with the boys other friends say are cute. You don’t have to be my best friend for me to sleep with the boys you like. Boys who won’t dance with April. Boys who only want to be friends with Jess. Dozens of boys. I don’t know why.

“Mmmmm, imperfection? You know, I don’t know Tammy. Imperfection? I mean, it’s just a scar.”

The teacher stands free of the wall. He walks, looks at my belly whole and my belly healed. Wonders what’s imperfect. He tilts his head. Touches his own face.

I never let anyone touch my scar. It’s old. I’ve had it since I was a child — my appendix festered all quiet in my belly. It barely even hurt until it ruptured, and then the infection. They left me open for days.

I don’t ever touch my scar, but when I do it feels numb and painful. Not where the scar is. Painful in my fingertips and up my arm. Painful in my legs. Painful, somehow, in my lungs.

I never come with any of the boys. I fake it, of course. I wish I could come because that’s what the girl I am does. She moans when they touch her. She comes and easily and it’s easy.

Once. Once I came while Joseph murmured about Elm. I’m fucking him face to face. I had all my clothes on. He lay on his bed by the window totally naked, one hand stroking one hand over his eyes. I’m holding his cock and I can see his face and I’m fucking him. I sat in his forest green papasan chair in the corner, my hand down the front of my zipped up buttoned tight jeans, a poster of Albert Einstein on the wall behind me. Albert Einstein’s sad and hopeful eyes. I’m watching him get fucked by me. His mouth barely moved when he talked. He touched himself gently, more gentle than I thought a boy would ever be with his own body. What I could see of his face twitched and winced. The face of a prince? A boy king.

What’s wrong?

“Maybe if it were big, but. Although… I think you’re on to something. I mean, keep going, Tammy. Keep going…”

This is a work-study job.

I don’t have to speak and I don’t have to draw.

“Mmmm, maybe, like, maybe we’re attracted to the danger of it? Like, maybe as animals? We’re, you know, like — I don’t know. Something about survival?”

I have a scar or I don’t have a scar, it’s not up to me. I take my bra off or I put it on.

They might notice something about me that is true.

“Well, here’s what I think. Try this on for size: You all look, essentially, the same. Right?”

Before they stitched me closed one doctor brought in a hand mirror and asked if I wanted to see my insides. Inside I am pink and yellow. Inside I’m purple and impossible to recognize.

“I mean, your bodies haven’t been through much of anything, yet.”

Or I was. Who can know, now? Now that I’m scarred over.

“Later. Later you’ll unravel in strange and unique ways but for now I think you’re trying to find things that prove you’re different. Different from each other. I think your trying not to draw your own body.”

+

But Amy says,

“I think the opposite.”

We’re in a reading room in the library. The room is in a tower. To get to it we climb wood stairs that end at a stone wall and reverse directions and end at a stone wall half a dozen times. Soon Amy will read to me from her notebook and I won’t try to look at her, but first she tells me something about what I want.

“If you draw a scar or don’t draw a scar, if I draw your unraveling and it looks like my unraveling or if I draw my unraveling and it looks like nothing anyone has ever seen — I think we’re never drawing difference.”

Step, step, step, reverse directions. Step, step, step, reverse directions. The room has a huge sunburst window that opens one whole wall to the sky and pillows we pull from couches to make the floor softer where we lie in the light. Light in expanding slivers. Amy says,

“Every picture is a picture of us. We always draw ourselves.”

We lie back to back. I think I feel her spine against my spine. I think I feel the spot where I stop being me and she starts being her. I think I feel the tiny space that holds us separate.

“Even when we aren’t drawing. Even when we’re lying still, like this. Always.”

But I can’t tell for sure.

+ + +

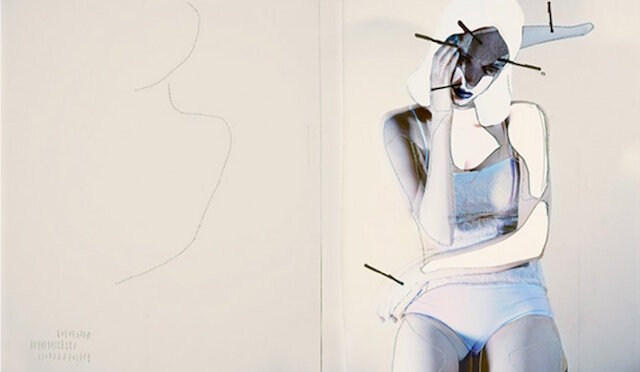

Header image courtesy of Jean-Francois Lepage. To view his Photographer Feature, go here.

Laura Green lives in Portland Oregon. She’s working on a memoir tentatively titled Bastard Child of a Renegade Nun, excerpts of which are published on the Hip Mama blog, Vinyl Poetry and Tin House's Flash Fidelity