Interview: Janice Lee

I first started seeing "ghosts," or spirits, or otherworldly presences, when I was a little girl.

In Janice Lee’s writing we are taken deep into what it can be to exist…

How we move through emotions, contradictions, explorations; how our psyches and bodies react to the world around us as well as our own experiments. Her work often includes philosophy, gatherings of work she has read and expands upon in her examinations and wisdoms, and those realms that we move through besides what most would consider “reality”. She has the innate ability to touch on in writing what it feels like to enter these other realms we so often inhabit, in which most of us are taught to shut out and ignore. The realms in which we may reclaim in order to create, seek, grow, and embrace our entanglement with everything.

It’s exciting to be in this space with her and feel a recognition that what may feel like our shadow selves, our “crazy” selves, our alien selves are such significant parts of our being that are showing us something dominant. And then more specifically, how does death make us more alive?

I read the first three pages of Imagine a Death several times before I continued with the rest of its pages. It was like a ceremony that I needed to exorcise some kind of stuckness I was experiencing at that time and this was the only way it would be released. I was feeling this tense locking of my limbs like how it feels when you peel garlic and want to punch someone. A desire for release. I read those words over and over until I felt that release. It was such a unique experience to have while reading a book. I was immediately hooked, and I wanted to hug her right then.

An excerpt that embodies this is on page 13:

“There was a visible burden on his back, that sunk-in posture like a word that likes to repeat itself until it loses its meaning, an ominous regret that continues to manifest in sores or in urges to smoke just one more cigarette, just one last and utterly glorious drag.”

Imagine a Death (Texas Review Press, 2021) can be found here. And Lee’s upcoming collection of poems, Separation Anxiety (CLASH Books, 2022) can be pre-ordered here!

And now it’s my pleasure to present…

a conversation with

Janice Lee

+++

NAILED: Imagine a Death starts off flying straight into the substratum of being human. All in the first sentence we are pulled into the character's sleep, dreams, nightmares, worries, fears, loves, and appreciation of beauty. Now, the first sentence is carried through into page three. We don't get the expected "relief" of a period until then. I was mesmerized by that tension immediately. You, the author, were asking so much of me as soon as I began reading. To be patient, present, allowing. I read that first part several times before I continued the rest of the book. It was something that I have mad respect for. At what point did you decide this was an element of how this book was going to be structured?

Janice Lee: The first sentence of the book is also coincidentally the first sentence I wrote. It one day just kind of poured out like the slow dripping of syrup out of a glass bottle, and I had no idea where it was going to end. But it felt important to keep that messiness and viscosity intact. For a while, I was spinning my wheels a lot with the first draft, so that first sentence got read and reread over and over again. It was always my entrance point back into the text when I sat down to write. It's definitely undergone a lot of revision and reworking, but the essence of the sentence is still there. With some minor changes, it's basically the first sentence that felt like it needed to be released in order for me to even begin to think about what it was I was even writing about in the first place.

N: Another narrative element that is uncommon in what we are used to in literature is your ability to change point of view, not only from chapter to chapter, but also sentence to sentence. This isn't a messy draft-like accident however, it is obviously intentional and free-form. It is as though you are making a statement that sometimes we write and change how the perspective is because it makes sense in our bodies and how we actually think as humans. Our experiences aren't all one-sided, usually. Is this something that happened naturally and you just went with it, or was it planned? Did you have you fuss with this during editing to make sure it flowed, or did that part just naturally happen?

JL: It definitely just happened, and when I realized it was happening, it took some time to articulate to myself why it was happening. You're totally right that I'm making a commentary on POV itself, its limitations, especially in fiction, its conventions and expectations, but I'm also enacting how vantage point is never fixed. Even in reality, I don't ever feel like I'm literally looking out into the world from a single point inside my head somewhere. I can feel my awareness moving, roaming. The way I move through the world doesn't fall into the confines of any single kind or consistent POV. I think this feels strange for a lot of people in Western culture. There is a definite self, a definite "I," we are separate and individual beings, and we interact with objects in the external world that affect our internal terrain. But this isn't how the world works for me. People, beings, the environment — there isn't actually as much separation between all of these things as we think there is, and any encounter is an encounter with everything else and the self and the self in relation to the everything else simultaneously.

N: What are some of your ceremonies for when you write? Do you listen to music? Do you make other forms of art to get your creativity juicing?

JL: My writing practice has changed so much. I used to write with very little ceremony. I would have headphones, music (for Imagine a Death, I exclusively listened to Russian Circles for the entirety of writing and editing the book), coffee or tea. Now I sometimes listen to music. I actually do a lot of "writing" while I'm outside walking. The slow, meditative movements and being outside helps me connect things together and settle into language in a particular way. So I might compose in my head and remember what I can later, or jot down notes in my phone. Meditation in general is a huge part of my process now: breathing meditations, but also journeying. Connecting with my spirit guides and ancestors. Flower essences, teas, and card readings also have been really supportive of my practice. I will admit I have been "writing" very little recently. I meditate and am present and sit and walk and listen and feel, but I've been translating less and less of my direct experiences into words on the page.

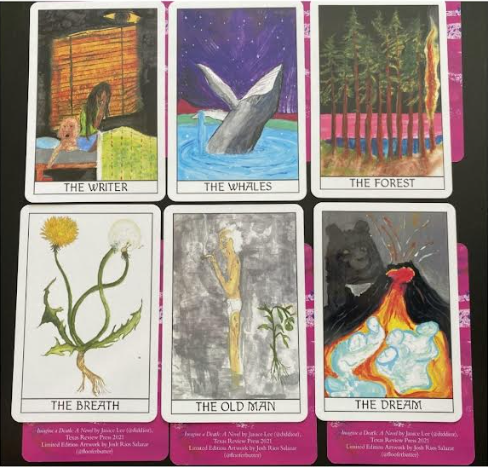

In honor of Imagine a Death, these beautiful, limited-edition tarot cards were created by Josh Rios Salazar (Instagram: @flooferbutter).

N: Your use of compelling and useful information about the earth and the natural world as metaphors makes me giddy when I read your work. I love learning new things while reading books! On page 179, you write a part about the requirements of ethylene to induce senescence in order for tomatoes to survive and ripen. This was very fascinating to me. The metaphor here made me yell out loud, giddily as I read it over several times! And may be my favorite part of this book. The way everything is necessary in order for the process of life. Even smoke, even death. When you were developing this book, was this something that inspired it all, or was it something you discovered along the way? What is your process for researching scientific truths?

JL: The tomatoes are totally inspired by actual tomatoes I was trying to grow in my garden. When I first moved to Portland and wanted to start a garden, I made a decision to just learn by doing. Usually when I start something new, I can get rather obsessive about research, about doing things the "right way," but I didn't want to get in my own way, and I also wanted to develop relationships with the plants, to allow them to tell me what they needed and to trust my intuition rather than relying on a more external system of rules. This meant though that I was willing to make mistakes, and that I would research things only as they came up. So when I began having some difficulty with the tomatoes, I began to research a little bit about the process of ripening tomatoes, what conditions they need, how people artificially induce ripening, etc. And then because of that research I became more interested in botany generally, and took an online course in Plant Biology where I learned a lot more about the specifics of basic plant biology, plant senses and development. I love researching in general, and I love learning. Many of my book projects have either been the product of, or led to, obsessive investigations. Currently, I am in an obsessive research phase about the lost land of Lemuria...

N: Your relationship to hauntings and ghosts is something I appreciate about your writing. The intimacy we have with various forms of hauntings, and how some are created by ourselves unto ourselves, and how ghosts don't have to be this spooky element that we "may" experience, but rather exist beside us and if we allow ourselves to see it, we may see so many other terrifying things as beautiful, and/or even just AS they are. When did you first realize that you had this kind of relationship with this realm?

JL: I first started seeing "ghosts," or spirits, or otherworldly presences, when I was a little girl. I didn't really put a label to these presences then, mostly because there wasn't a need to categorize, but I also didn't know that these categories even existed. I would often have prophetic dreams that I would share with my mother, and she would describe me as having access to another kind of "sight." It mattered that she really trusted and believed my visions. I would hear things that no one else heard, magically find lost objects for strangers, and even my grandfather sensed a kind of expansiveness in me, but I don't remember the language he used now. As I started to grow older though, a lot of this went away. Some of that was intentional, I think I kind of suppressed it to be more "normal," and as I was pressured into studying medicine and becoming a doctor, I tried to find more intellectual ways to understand the world. But after my mother passed away, a lot of that "sight" started to come back, except that at that point, I was a very skeptical adult who had studied too much Western science and philosophy, and so didn't know how to reconcile it all. So it's been a long journey back, a journey back home, and a series of synchronous encounters, devastating losses, the wisdom of plants and my dogs, and many teachers, who have all helped me understand myself more in relation to the world. The ghosts for me, are both "real" and "not real," and also, it doesn't matter. I think we place too much emphasis on what is "real" and our preoccupation with trying to define the boundaries of experience just limit what it is that we're already experiencing, sensing, and intuiting all the time.

N: You embody being a multi-faceted artist human, and are not afraid to exist outside a box or brand of what you create. Writer of fiction, philosophy, poetry, healer. So many of us are taught that we must create a "brand" in order to be marketable and consistent. I believe this can stifle some from creating at all because it can be quite overwhelming. What do you have to say to people who are afraid of being multidimensional as artists?

JL: Our fear of being multidimensional as artists is also our fear of being multidimensional as human beings. And of course there are so many factors and considerations that play into that, the way we were trained to survive in capitalist white supremacy, everything we are told about how to be successful. But if our success isn't aligned with our true values and views of the world, is it really success? If we feel like we need to participate in all these processes that just spread toxicity and wrong perceptions and actively harm both the physical and mental health of our peers, we need to ask ourselves, what are we really doing, not just as artists, but as living beings.

+++

Janice Lee is also a teacher, and I highly recommend working with/learning from her in the safe and generative spaces she creates. She’s also sharing daily writing prompts on her Instagram and Facebook pages throughout this year for those who wish to explore deeper in a more introverted manner.

Learn more by visiting her website and Instagram: @diddioz

Janice Lee (she/her) is a Korean-American writer, editor, teacher, and shamanic healer. She is the author of 7 books of fiction, creative nonfiction & poetry: KEROTAKIS (Dog Horn Press, 2010), Daughter (Jaded Ibis, 2011), Damnation (Penny-Ante Editions, 2013), Reconsolidation (Penny-Ante Editions, 2015), The Sky Isn’t Blue (Civil Coping Mechanisms, 2016), Imagine a Death (Texas Review Press, 2021), and Separation Anxiety (CLASH Books, 2022). A roundtable, unanimous dreamers chime in, a collaborative novel co-authored with Brenda Iijima, is also forthcoming in 2022 from Meekling Press. An essay (co-authored with Jared Woodland) is featured in the recently released 4K restoration of Sátántangó (dir. Béla Tarr) from Arbelos Films. She writes about interspecies communication, plants & personhood, the filmic long take, slowness, the apocalypse, architectural spaces, inherited trauma, and the Korean concept of han, and asks the question, how do we hold space open while maintaining intimacy? Incorporating shamanic and energetic healing, she teaches workshops on inherited trauma, healing, and writing, and practices in several lineages, including the Q’ero, Buddhism, plant & animal medicine, and Korean shamanic ritual (Muism). She currently lives in Portland, OR where she is an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Portland State University.

She can be found online at http://janicel.com and Twitter/Instagram: @diddioz.