Interview: Artist Laurie Hassold

Artists and scientists are similar in that they seek answers to the big questions.

I came across Laurie Hassold’s “Lady in Waiting” sculpture last year in a southern California gallery called Art Cube, and it immediately drew me in with its detailed, fragile intricacies. While it worked some strange beauty therapy on me, hanging on the wall like a huge piece of jewelry, there was also something dark and somewhat wicked about the work, as if this gorgeous totem was something that a cunning demon composed from a dead woman’s organs.

I stared at the piece for a long time before inquiring further about the artist and her work. I emailed Hassold on behalf of NAILED, and when I found out she’d done some performance art featuring her own blood, I asked for an interview. Below is my candid interview with Hassold (who is unbarred and creative even in her answers), as well as several small galleries of her sculptures, all truly remarkable pieces of art.

+ + +

NAILED MAGAZINE: How would you describe your personal and emotional relationships to the work you make? How do you feel while you are making it, and when it is finished?

LAURIE HASSOLD: I wish I could say that I sculpt in a sustained state of creative fury, but my process is fraught with highs and lows. Much of the time, I feel like I’m stumbling around in the dark, trying to get my eyes to adjust, feeling my way through the terrain, and often stubbing my toe in the process. Making decisions on how a form will evolve takes me a very long time… I temporarily attach things, then distance myself for awhile, before making the decision to go permanent. My process is fairly intuitive, therefore, there can be many incarnations before a sculpture is exhibited. Each time I say “no” to one direction, it feels like a little death for all the other possibilities. I’ve always been like this… listening to many sirens, immersing myself in endless research, potential and creative play.

The most joy I feel when making a sculpture is when a certain curve or flourish takes hold, and I can almost hear it through my eyes… an audible movement, like music. This is when the piece starts to “yearn.” I give it so much of my own eye juice—scrutinizing it in a full-length mirror—looking for any imperfection that corrupts the form and keeps it from being believable. I want the form to look back at me with a little recognition. I want it to mirror in a tangible way, all of the yearning I feel inside. Until it is able to see me with a sentience all its own, it can’t possibly see inside itself—therefore, it isn’t alive.

When it does start to wake up, I have a potential playmate. We can whisper little secret jokes to one another… look for mementos of things that haunted us from childhood, and continue to color our reality. The sculptures are almost like lungs for my emotional, physical and psychological experience—it slowly inhales all of my thoughts, feelings, musings into itself while I work on it, and when it’s full, exhales out freshly filtered visions of these experiences in tangible form. There are so many random associations that surface while I’m working on a piece, things that play through my mind like radio waves traveling through time… my childhood crush on Dave Bowman in the form of astronaut miniatures, little statuettes of Rococco courtesans that bring back bittersweet memories of failed relationships, and my parents divorce, and even schmaltzy Disney toys, like Stitch’s ears from the movie Lilo and Stitch, a movie which never fails to put me right back to childhood abandonment issues. Of course the ubiquitous dinosaur skeletons and animal bones that for me are darkly satisfying memento mori. As the dinosaurs went, so too shall we, kind of thing. Being a rather romantic nihilist, I find comfort in ruminating about a world without humans. Feelings of nostalgia, loss, alienation—all remnants from my past, as well as the collective past. How can we exist knowing we will die?!

My work makes me feel connected to something more complex than I am—something bigger. That sounds metaphysical, and I want it to be true—that we are star vessels and it all will make sense some day… It’s some sort of language I’m trying to understand and translate that makes my brain and heart hurt—a language that could help me become part of something much larger than myself, but that I may never be able to decode.

I can’t say if the work ever feels finished to me, even when its already been exhibited. A few early pieces have been cut apart—and some discarded altogether. This is painful, and freeing at the same time. For me the work is always striving to become, and never truly being. This is the paradox I have experienced most of my life, so I suppose, without sounding too trite I hope, that the sculptures are a way of making this state of flux and impermanence more tangible, in order for me to be able to hold still, transform and transcend my own emotional state.

FREEDOM, ANGST, SELF DOUBT/CRITICISM, DEPRESSION, ELATION, DISCOVERY.

My process is riddled with highs and lows—punctuated by long periods of putting one foot in front of the other drudgery. Fear and Epiphany seem to comingle with avoidance, myopic obsession, procrastination, and breaking point—usually brought on by deadlines!

NAILED: As a young girl, spending time with your father in his medical laboratory, you were encouraged to visually analyze parts of the internal body. Did seeing your own blood as a child make you feel alien to yourself or create a sense of understanding? How does that feeling compare to the performance art using your own blood that you’ve made as an adult?

HASSOLD: I was so young when I first looked through a microscope at my own blood (and urine!)—it’s all very abstract to me now. The overarching feeling I get when I think about it, is one of shock, and maybe even a little repulsion. I thought I was a solid thing—a whole—and what I saw through that microscope made me feel fragmented. What I perceived my body to be was actually made up of tiny squirming things. I couldn’t recognize myself anymore, and it made me feel permeable, less safe. I would say the experience definitely made me feel more alienation and less understanding.

The real mind blower was watching the hysterectomy at age 11. Feeling organs as they were cut from a woman’s belly. Watching the surgeon’s hand go up inside and underneath the skin—move around to check the organs to see if any were enlarged. I never forgot the courtesy appendectomy he performed, and how the appendix looked like a squid. Nowadays this would not have been possible—too much liability to do a procedure that wasn’t scheduled and consented to….

As an adult doing performance art, I felt liberated. Of course before and at the start of a performance, I am consumed by fear and anxiety—stage fright. The ego is ruling you at this stage—fear of boring the audience with navel gazing antics. Then as I get immersed in what I’m doing, time starts to slow down for me, and I become less aware of my surroundings—three hours can feel like 3 minutes!

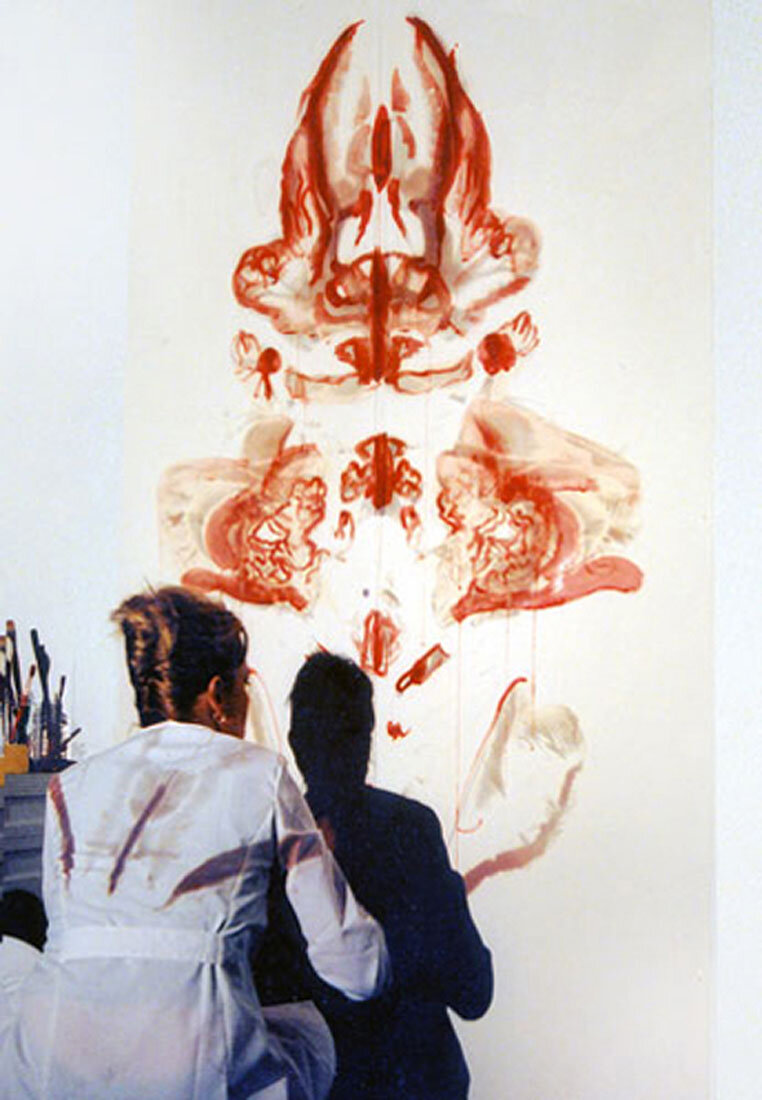

The whole thing started as an accident—I cut myself working on a sculpture, and on a whim, squeezed some blood onto a piece of paper and folded it. It was like a gift seeing that Rorschach image appear! I kept doing it, and was gratified to see all the variety of insects, animals, plants, bones, dolls, warriors, goddesses—archetypes hiding in my blood. It was a way to make my fragmented view of my body whole again.

The symmetry gives an orderly structure for all the sub levels of anthropomorphic imagery to cling to. As humans, it’s our nature to look for order in chaos—we want to understand, recognize, feel safe. It’s wired into our limbic brains for survival. My singular non-linear nature feels constantly about to fragment into the stratosphere, and so I crave order and direction. It is a constant struggle for me to stay on one path and follow it to its logical conclusion without becoming distracted by numerous branching arteries along the way…symmetry provides me with an armature for safe exploration.

The Rorschachs’ symmetrical nature provides an organizing influence, something that can be read as a whole, then peeled back to reveal all of the myriad layers and sub levels of just under the surface.

NAILED: How do you go about sourcing or choosing materials for the more intricate portions and details of your sculptures? What are some of your favorite processes and why?

HASSOLD: I have collected a lot of random objects over the years—figurines, toys, jewelry, antique hardware, wasp’s nests, insect exoskeletons, snake, rat and bird bones, on up the food chain to raccoon, bobcat, coyote, deer and cow bones. Friends who know my fondness for dead things often give me presents, and I recently came home to find several zip lock baggies filled with wasp’s nests and an entire human skeleton on my doorstep! Regardless of the source, I choose objects that instantly attract or inspire me. The inherent function is not usually important, but can sometimes add to the meaning of the work.

Having a soup of all this stuff around allows me to try out different inhabitants for a developing structure. It can take weeks or months of digging around to find the right fit. In the meantime, I sculpt intricate matrices with wire and resin clay, striving to make sense out of a form as it intuitively evolves. In some ways it feels like all I’m really doing is making elaborate fossilized nests for smaller life forms to take up residence. This process is slow, and is a little like being lost, trying different paths over and over until you finally recognize familiar surroundings and realize you’re home.

Even after decisions are made, there is the risk of an object getting swallowed by the claustrophobic sculpted layers, rendering it unrecognizable in the end. These hidden bits add history and DNA to the work, however, like the geological clocks of sedimentary layers to be excavated by some future species in a post human world. The congested nature of my work, at times makes me yearn for the clinical and scientific, which is why astronauts and lab coat sporting scientists started appearing in the forms. Artists and scientists are similar in that they seek answers to the big questions, where we come from, how we got here, and what our place is in the cosmos. My tiny assertions peeking out from the overwhelming matrix of existence are allusions to the fact that answers to these questions always seem to be just beyond the limits of the best and most brilliant human brains.

NAILED: When was the last time you NAILED it?

HASSOLD: Does any artist ever feel like they “nailed it”? The yearning for resolve and reaching a level of skill and insight previously not thought possible is always part of creating work; however, my personal criteria for that level of satisfaction constantly evolves and I keep changing the rules while I’m still playing the game. When I look back on previous work, I do see areas where I still think I “nailed it,” and there are pieces I wish I still owned, like Lost Spring, What the Tree Remembers, and Explaining the Future to an Extinct Hare. But if these works were still in my possession, the worm of my somewhat perverse creative process might turn, and they would run the risk of dismemberment and cannibalization into new forms.

Laurie Hassold was born in Louisville, Kentucky, but has spent most of her life in southern California. She shares a home and studio with her husband, painter Jeff Gillette, and teaches art and design at Orange Coast College, Irvine Valley College and Cal State Fullerton University. Selected museum exhibitions that have featured her work include Confronting Mortality with Art and Science, at the Historic Halls of the Antwerp Zoo (Antwerp, Belgium), The Shack Show at Laguna Art Museum (Laguna Beach, CA), and Extreme Materials II at the Memorial Art Gallery (Rochester, NY). Past solo exhibitions that she is particularly proud of include Exorb…and one day we didn’t need to breathe at Grand Central Art Gallery (Santa Ana, CA), Supernature: A Post-Human Fairy Tale at Track 16 Gallery (Santa Monica, CA), and Nostalgia for the Future at Art Cube Gallery (Laguna Beach, CA). She is currently working on an upcoming solo exhibition for Bert Green Fine Art in Chicago, Illinois that will open in autumn, 2016.

If you are interested in a piece of art, or would like to contact the artist, please email her at lauriehassold@hotmail.com.