Memoir: Death Before Cell Phones by Cari Luna

“I cling to the fractured memory of those gifted hours”

Memoir by Cari Luna

+++

My father died before cell phones. At the time I couldn’t have understood what a gift that was. Not his death, obviously. I would take that back. I would undo that in an instant with little regard for what havoc it might wreak on our theoretically fragile time-space continuum. Of course I would undo his death. No, the gift of it was the lack of instant accessibility, the fact that I could not be immediately reached regardless of where I was, when it happened.

On May 10, 1993, I was a sophomore at Bard College in upstate New York. I was often gone from my dorm room, where my telephone and answering machine lived, from early afternoon until well into the evening. My dorm was in North Campus, about a twenty-minute walk from the classrooms and the dining hall. I tended to hang around main campus between afternoon classes and dinner.

After dinner, my friend Megan and I went to study in one of the classroom buildings. We staked out a room and settled down to work, then Megan saw Mike, a friend of hers, go by in the hallway. I’d harbored a crush on Mike since the beginning of freshman year. (I think, after twenty years, it’s okay to now divulge this secret. Mike, I had a crush on you. There. Now it’s all out in the open.) Megan called out to him and he came in and they talked for a bit while I sat quietly and blushed.

A while later, we saw him walk past again. Megan whispered, “Follow me.” We snuck into the classroom where he’d set himself up, and stole his backpack. He came looking for it and...

And I don’t remember what came next. I know that there was laughing. A lot of laughing, all three of us together.

It’s funny...all these years I’d told myself I had perfect recall of the details of that evening, that it was saved whole cloth in my memory, the precious final hours of my innocence. But now that I’ve set about recording them here, I find that the night isn’t immune to the usual deterioration of memory. It comes back to me in postcard snapshots, moments I’ve retained that stand in for the whole. What I remember: the forbidden feeling of the empty classrooms after hours; Megan’s comic, overacted caution as we snuck down the hall to steal Mike’s bag; Mike’s laughter: full, open-mouthed, generous.

When I got back to my dorm room that night, the red light on my answering machine was flashing. I don’t remember how many messages there were from my mother, her anxious voice asking me to call home, but there were many. She called again as I was standing there. My father had had a heart attack at work that afternoon, she said. He’d called her, not feeling well, saying he was coming home early. He stopped into a coworker’s office on his way out, vomited, and dropped to the floor. His heart had stopped. The coworker performed CPR, but didn’t succeed in reviving him.

I don’t know why my mother gave me all this detail. She was in shock, I suppose. I have long wished to erase that fact of his vomiting from my memory, the shame I felt for him, being made so vulnerable in front of a coworker. So vulnerable away from home, away from us.

It took the EMTs fifteen minutes to reach him. The damage to his wondrous brain was, by then, done, though we didn’t know it that first night. We hoped, of course, that he would recover. We expected him to recover. Because how could he not? He was only fifty years old. I was nineteen. My brother was sixteen. We needed him, and so he would recover. Anything else was unthinkable.

My father was revived by the EMTs and transported, still unconscious, to a nearby hospital. His heart stopped twenty-six more times that first night. I wonder sometimes why they didn’t just let him go.

They didn’t just let him go because he was only fifty. You don’t just let a fifty-year-old go like that. But I think of his body brought back by force again and again. I think of him cut open, ribs spread, on an operating table, and I don’t know that it was worth it. Do they ever succeed in bringing someone back whose heart is so determined to stop?

He never regained consciousness. He went on in the hospital, comatose and brain damaged, on life support. When I visited, the body in the bed was alien to me. It barely resembled him at all. He was already gone. After three weeks my mother made the decision to turn off the machines.

It was the first truly tragic thing that had happened in my life. I’d lost three grandparents by that point, but they were old, and not necessary in the way a parent is. The usual childhood and teen indignities aside, I’d had a comfortable, unchallenging life. That life ended with the phone call from my mother that I finally answered. There was my life before my father’s heart attack, and then there’s been everything that’s come after.

My poor mother, unable to reach me for all those hours. Now, as a wife and mother, I think about how powerless she must have felt, how alone. But for me... There is nothing that I could have done to help my family had I known about my dad’s heart attack sooner. My cousin still wouldn’t have come to pick me up and drive me to the New Jersey hospital until the next morning. (The Spin Doctors were on endless repeat on his car’s cassette player and I will never hear those songs without recalling the numb terror of that ride.) Being available for the first phone call would only have brought me to grief sooner.

I cling to the fractured memory of those gifted hours. My life as I’d known it had been blown apart, but I remained blissfully sheltered from it, laughing and playing with a good friend and a boy I had a crush on. And because of that, that friend and that boy will always be dear to me. Megan remains a good friend. Mike and I never did become friends and I’m not in touch with him now. But still, he will always be one of the two people who shared my last hours of innocence, and I will always be grateful to him for the simple fact of his having been there, smiling at me. My old life closed with sweetness and hope. I can’t regret that.

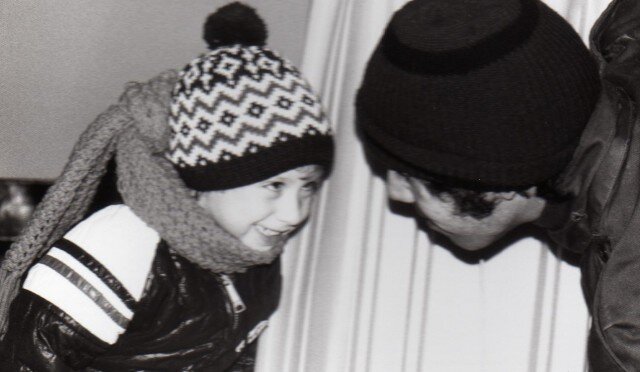

[Photo of Luna and her father, courtesy of the author]

+ + +

Cari Luna received an MFA in fiction from Brooklyn College. Her debut novel, The Revolution of Every Day, was named one of the Top 10 Northwest Books of 2013 by The Oregonian. Her work has appeared in Salon, failbetter, Avery Anthology, PANK, and Novembre Magazine. New York-born, she now lives in Portland, OR. Visit her official website here.